Marcelo Brodsky, Photographer and Poet

Silvia Levenson, Visual Artist

Ernesto Pesce

Visual Artist

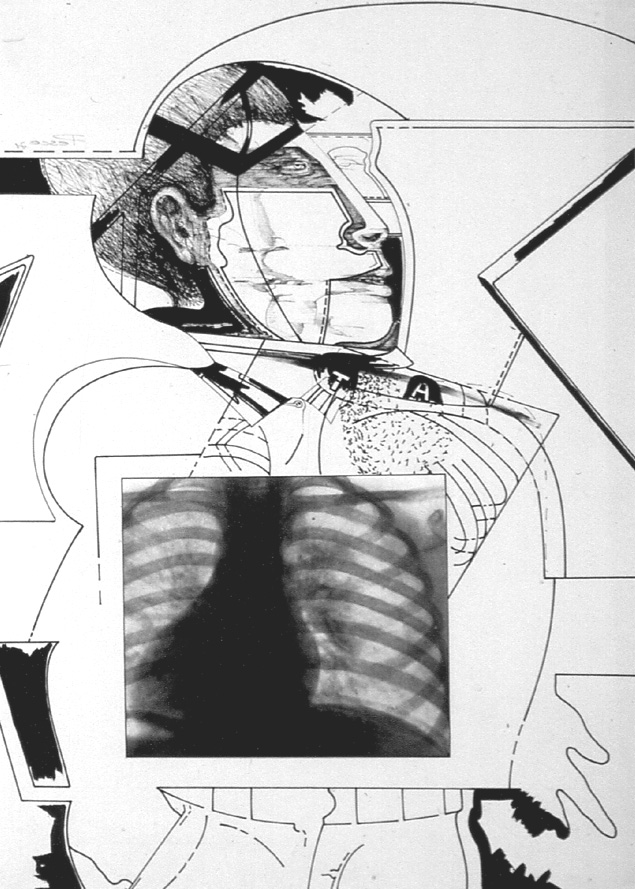

Ernesto Pesce is a visual artist, primarily drawing, painting, printmaking, and working with objects. He has lived in Buenos Aires his entire life.

Once cosmopolitan and a cultural melting pot, called the Europe of Latin America, Ernesto’s homeland changed by the mid-20th century. The military’s “Liberating Revolution” overthrew Juan Peron’s government in 1955 when Ernesto was a child. The government was conservative, restricting political and cultural activities. By the mid-1960s when Ernesto was a student, he produced art that reflected his resistance to the dictatorship. But he was careful and not outspoken about his ideas, painting symbols to hide their true meanings.

Eventually, the dictatorship weakened and the exiled Peron, beloved by many in Argentina, returned with his new wife Isabel in 1973. Democratic elections were held that year with Peron recapturing his presidential office. Peron’s term was marked by extreme and violent conflict between Peronist factions: worker unions and Montoneros on the left and conservatives on the right. Calls to repress the leftists, death squads targeted radicals. Meanwhile, the Guevarist ERP, opposed the Peronist right wing and engaged in guerilla tactics against the Army and Ford Motor Corporation. A year after Peron’s third term, he died on July 1, 1974. Isabel Peron succeeded him for three years until the military junta took over and a new reign of terror swept Argentina in 1976. The new dictatorship set out to restore the country and rid it from all insurgent elements. Anyone thought to oppose the government risked their lives.

By this time, Ernesto was a professional artist and not willing to risk his life by representing any resistance against the junta. Instead of painting about the events unfolding during this “Dirty War”, Ernesto turned to reflections about his Italian grandparents who immigrated to Argentina in 1900. They were artists who painted murals of churches in the Piedmont area in Italy. When they immigrated to Argentina they could no longer continue their art. As a tribute to his grandparents and their sacrifice, which allowed him to be an artist, he produced a series called Immigrants that told the story of the massive immigration in the 19th century Argentina.

The dictatorship that terrorized Argentina for several years, fell in 1983. Argentina returned to democratic society. No longer were its people turning a blind eye to atrocities or living in fear. It became what it once was several decades earlier, a melting pot where people of different races and religions lived together. In 1988, Ernesto married a young artist, the sculptor Mariana Shapiro. Their marriage was a bond of art and a blending of cultures. Mariana’s grandparents were Jewish, immigrating from Russia. At an early age, Mariana was a recognized artist and received many prestigious awards for her work. One of the many important works she produced was in 1995, a monument for the victims of the AMIA bombing in the Jewish cemetery in La Tablada. In designing the monument, Mariana was inspired by the one surviving building from that tragedy, the AMIA library. For her, its survival meant that ideas, religious beliefs, acts of solidarity, and love for fellow human beings cannot be destroyed by a bomb or by death.

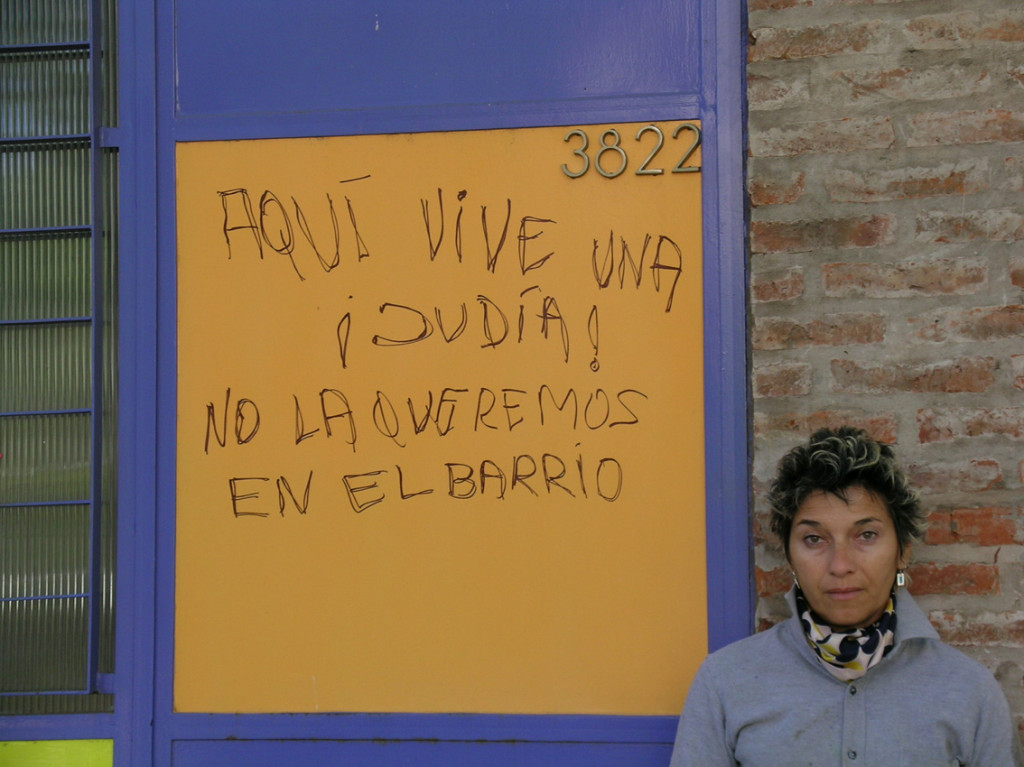

For 20 years Mariana and Ernesto lived in a neighborhood of peace among friends. In 2005, Mariana and Ernesto woke up to find on the door of their house graffiti that read “Here lives a Jew, we do not want in the neighborhood.” They never experienced an act of anti-Semitism. Mariana responded quickly, taking a photograph with her standing next to the graffiti. She made sure that everyone knew about this act of hatred. In return she received an outpouring of support and expressions of outrage. The authorities called her, the press published stories, and friends sent her emails. From all of this material, she created an art book, which she titled The Monster in My Neighborhood that was part of a group exhibition called “Books of the Artists“. Two copies of the book exist today. An art collector owns one copy and the other is on loan with a friend of Mariana’s who is an official of the AMIA. Mariana spoke out without fear.

Mariana died in 2006 at the age of 46.

Ernesto’s art has exhibited in Argentina, Venezuela, Peru, Chile, Mexico, Spain, France, Italy, South, Korea, Taiwan, Japan, and the United States. Ernesto’s recent works includes “Some Roads Leads to Strength” series (2007), which represents the idea that we can find the strength to live fully if we follow certain paths; “The Great Wall of China” series (2009) inspired by Jorge Luis Borges’ “The Wall and the Books”; “You Cannot Conceal Your Sowing” series/”You Cannot Conceal Your Tree Cutting” series (2009), using geometry and Google Earth’s imagery to convey the reality that we are being watched through satellites in our intimacy.

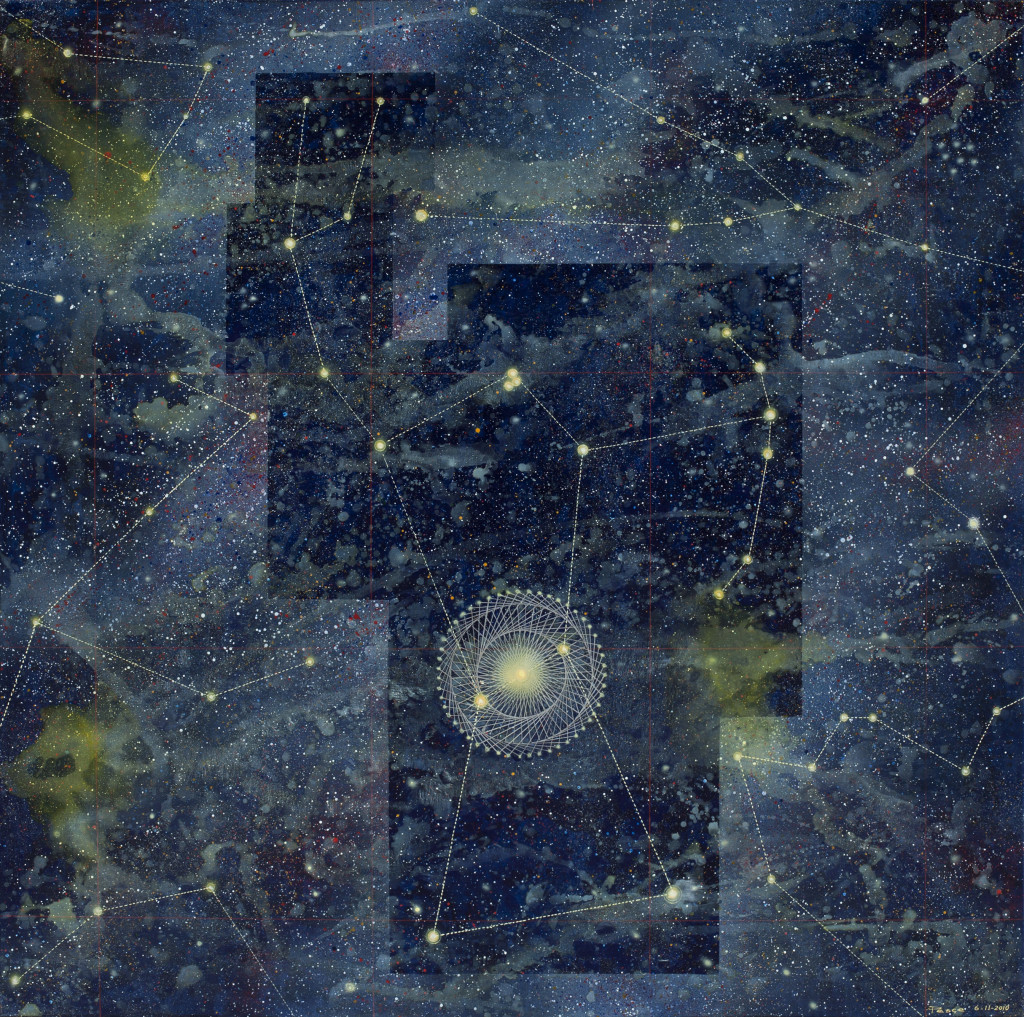

His recent “Soul Portraits (2011) symbolizes the wish his son Lautaro told him in 2006 after Mariana died. “The soul of my mother, Mariana was in the center star of the ‘Tres Marias’, in Orion’s Belt. Ernesto found a way to make the wish in an image.

Ernesto believes that our project is important because we should never tolerate any attack, no matter how small the persecution and discrimination against any person because of race, ethnicity or religion. At any time, anywhere.

Translation:

In 2005, on the front door of our house there appeared this inscription , “Here lives a Jew, we don’t want her in our neighborhood.” We lived 20 years in that place, we always had a great relationship with our neighbors. Something very strange for us to experience. Mariana quickly had a photo made of her standing next to this graffiti on the door and made a complaint to the police about the anti-Semitism. She also sent an email and the photograph to her friends. Eventually, they heard from a thousand people from everywhere around the world, seeking solidarity. The police reacted quickly. They put custodians on the door, to guard the door. The government authorities called right away, always with the message that any discriminatory act or anti-Semitic act would be reacted to right away, would be denounced.

And there was another aspect on the artistic side of things, an invitation to Mariana to participate in an exhibition “Books of the Artists”. Artists would create books where they would draw something, write something. So Mariana figured for this exhibition that she would print all of the emails they had received, including the photo of her standing next to the graffiti on the house’s front door. So she converted a regrettable act as an artist into an artistic work.

Translation:

Mariana created there (at the Tablada, the Jewish Cemetery) something very artistic about a very lamentable act that was related in this case to the library that AMIA had maintained. The sculpture has a plaque with Jewish letters, Jewish words on it—quotes. They are connected, but they are moving towards the heavens. So her message was that something essential cannot be destroyed.

Marcelo Brodsky, Photographer and Poet

Silvia Levenson, Visual Artist