Monirah Hashemi, Performing artist living in Sweden

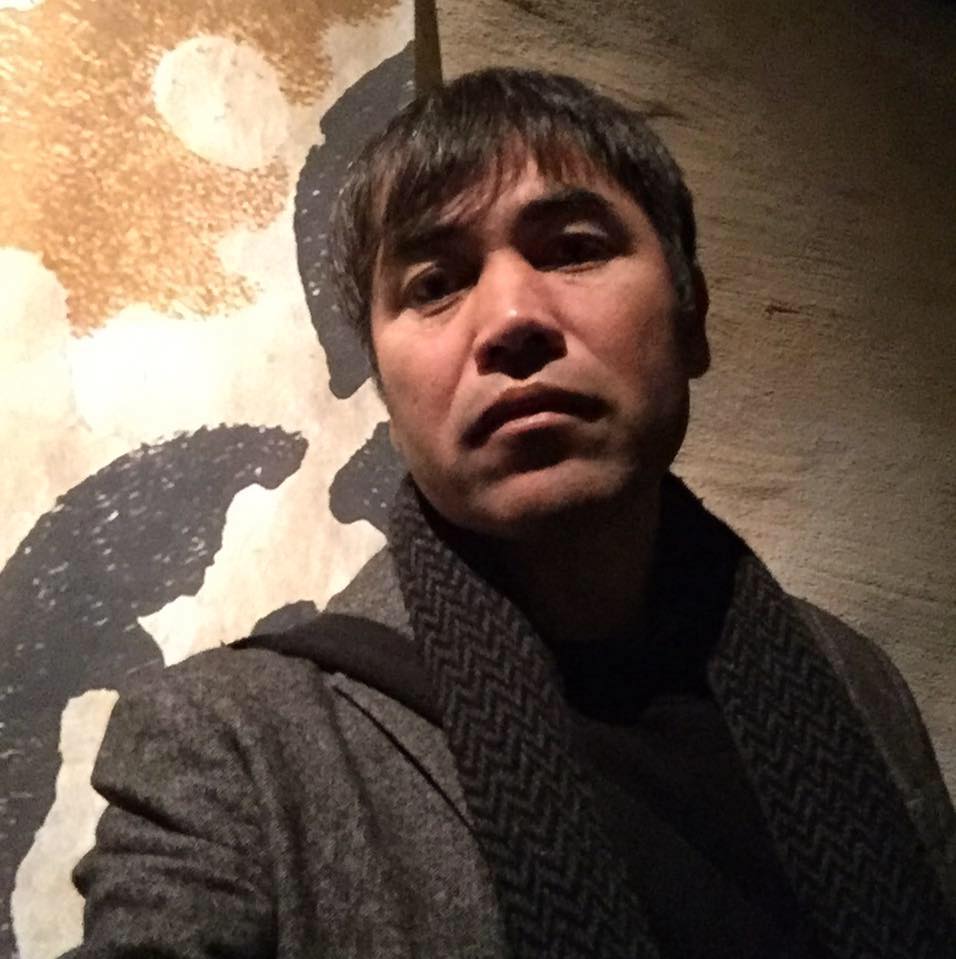

Asad Buda

Historian, Writer, and Artists’ Guide

Asad is a religious scholar, historian, writer, and guides other artists to express feelings through their art.

Asad did not enter this world with an easy life. Born in 1978 in Bamiyan, along the Silk Road in central Afghanistan, he lived among other Hazaras, a tribe of people who have been subjected to persecution, oppression, and genocide throughout its history. For his first 12 years of life, he survived the Afghanistan’s Mujahideen-Soviet conflict. When he was 18, he endured years of life under Taliban rule.

When he was only two years old, the Mujahideen killed his father over a horse. The Mujahideen needed the horse to transport weapons in their struggle against the Soviets. While Asad’s father refused to lend them his horse, they took the horse anyway. When they returned the horse, Asad’s father complained about its condition. In response, the Mujahideen threw his father off the roof of the house and killed him. Asad asked his mother what happened to his father. She gently answered that the angels took his father and brought him to paradise.

Shortly after Asad’s father’s death, his mother, who was not formally educated, was determined that her children, including her daughter, be educated. She enrolled them in religious school. When Asad started religious school, his lesson began with readings in the Holy Quran. Assad took interest in a passage on angels. He quickly was disillusioned. These were the angels who took his father away from him. He tore the pages out and burned them. The mullah at the school punished Asad. His mother, Leila, stood up to the mullah and protected her son. From that moment, he rejected Islam. Throughout his life, Asad is greatly influenced by the strength of his mother.

Not swayed by cultural and societal pressures to marry again, Leila refused to the proposal by her late husband’s brother. She preferred to be single, a stigma in Afghanistan, raising her daughter and three sons on her own.

Asad’s uncle was a member of the Mujahideen and sought retaliation for Leila’s rejection. He asked the Mujahideen to take away Asad’s family’s land and home. The Mujahideen came to Asad’s home, asking his mother to give them the deeds to the property. They brought the documents to the local court’s judge. The judge took the documents and escaped with them on horseback. His mother knew the route the judge took and ran after him. She was able to intercept him on his escape route, threatening to throw him into the Herat River and forcing him to give back her documents. Soon after, Asad, only 11 years old, and his two brothers were sent to prison. Asad explained, “A commander of Sipah party decided to grab our lands and take our proprieties documents. Me, my mother, and my two brothers resisted against him and defended our lands and proprieties. He couldn’t take our lands. They attacked, captured me and my brothers, tied our hands and took us into prison.” Asad was in prison for six months, his brothers for more than a year. While in prison, Asad learned the art of calligraphy from a security guard for the Mujahideen court. Every day he practiced his calligraphy becoming very competent, writing the stories his mother told him from The Book of Kings, called Shahnameh. While Asad is considered an expert calligrapher today, he does not like calligraphy because of the trauma associated to learning it in prison.

Asad studied Islamic theology in Qom, Iran. It was there that he first encountered Paul Celan’s poetry, which changed Asad’s perspective. He saw the connections between the genocide of the Jewish people during World War II with the atrocities perpetrated against Hazarans. The connection between Hazaras and Jews is not unique. It is believed in some quarters, that the Hazarans are one of the lost tribes of Israel.

He dug more deeply, studying other Jewish philosophers like Walter Benjamin, Theodor Adorno, and Max Horkheimer. Yet Celan remains the greatest influence on Asad, making him aware of how victims become rootless in the realm of reality, become nomads in their home, and alienated of their mother language. They live in what he calls the “In-Between”.

Asad is a consultant various artists, including the well-known Hazaran artist Khadim Ali whose paintings explore the moral themes of good and evil (as depicted above) and to the playwright Monirah Hashemi whose play Sitaraha – The Stars, tells the story of three women living under oppression Afghanistan from 130 years ago to the present.

While Asad describes himself as a historian and writer, he also defines his work as an “act of secrecy” and living in the “in-between”. The idea of refugees being “in between” is a recurring aspect of Asad’s activities. Recently, he organized some artists to create passports for refugees and others facing oppression—people without countries.

Asad continues to influence his people in Afghanistan. During the summer of 2016, Hazarans staged a peaceful protest in Kabul (above). They were upset by a recent decision to divert new power facilities away from their homelands, particularly in the Bamyan region. ISIS bombed the area, killing at least 80 of protesters. In the aftermath, Asad helped to organize the Enlightenment Movement, the name given to represent the electricity that would have provided the light. It also signifies Bamiyan, which means “The Place of Shining Light”.

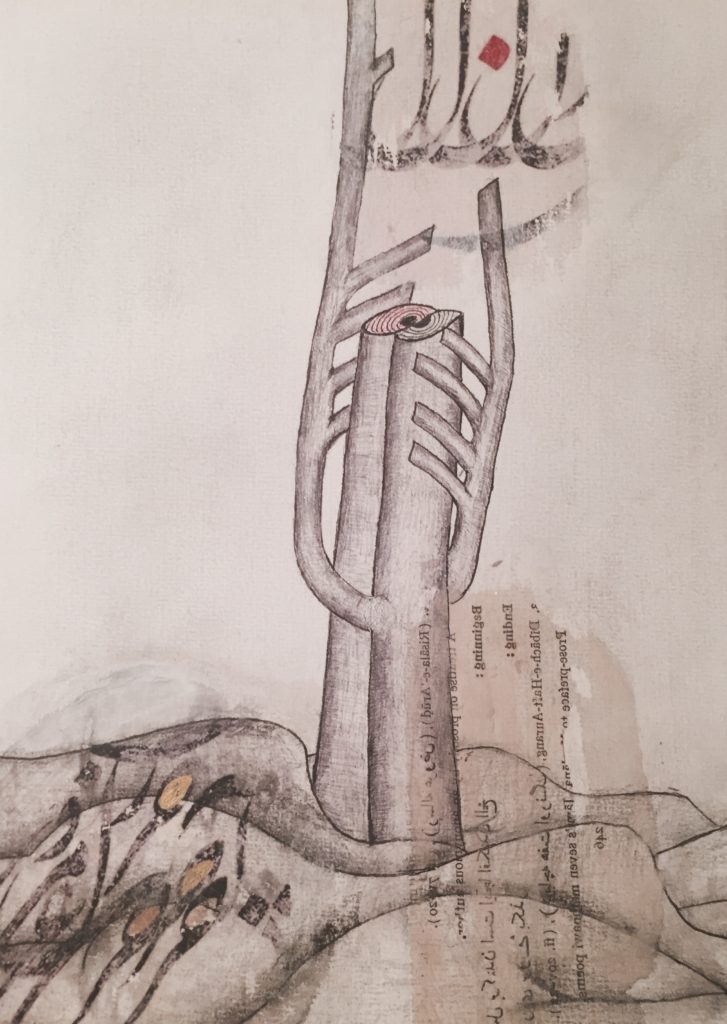

“The Movement of Light” (above) is a painting by Asad that captures the moment he heard about the ISIS bombing in July, 2016. He explained, “I received a message: ‘Blast in Kabul.’ I was shocked by the message, dropped my pen. Opened Facebook. It was all photos of dead bodies and blood in Dehmazang Square on the Facebook pages. I lost my words. I could not make sense of anything that came to me. I felt sick, a sudden fall. While struggling to decide what to think, what to do, or how to respond to the news, I found myself holding my pen again. I tried to write something. But words failed me miserably to describe my feeling. I drew two trees instead. Two beheaded trees hugging each other. They were kissing or perhaps they were weeping. I couldn’t tell. I just know that in such moments of horror and pain, we become mute and all we need is a hug. We become just like that WWII soldier who fled naked from war into his mother’s arms. All the world was screaming and I was really needing, love, arms, inner peace silence.”

Though Asad creates art— calligraphy, photography, and painting (as shown above)—he does not consider himself an artist. Rather, he guides others to express their feelings through their art. Typically, this involves saying things or creating representations that are not allowed in Afghanistan. For example, he organized school children to write and draw images regarding their feelings on canvases. He urged them to make these representations as “bad” as possible. These representations became the under-paintings on canvases for local professional artists who created acceptable works of art. Their messages were expressed and hidden in the professional artists’ works.

Indeed, light and enlightenment are recurring themes in Asad’s outlook on life. He chose for his name the alias “Buda” because it means light. He believes his people and others facing oppression are in the darkness and need light and enlightenment, which he expressed in a a poem he wrote to us after our interview with him in September 2016 (above).

Because of his activities, numerous fatwas have been issued in Afghanistan and Pakistan calling for his death. He cannot return to his homeland for fear of being stoned to death. He is therefore living in exile under an assumed name.