William Thapelo Mashaba

Write, Actor, and Director of Plays and Rap Musician Drama

William Thapelo Mashaba, known as Thapelo, is a writer, actor, and director of plays, as well as a rap musician. He is also a role model for the youth.

Thapelo was born and raised in Winterveldt once an Apartheid ghetto, located northwest of Pretoria, South Africa. He, his two older sisters, and brother are children of Apartheid survivors. Often children of survivors either absorb their parents’ pain and experience of abuse or they are resilient and become an agent of change. Thapelo is the latter. He is an agent of change for his family, his town, and his country.

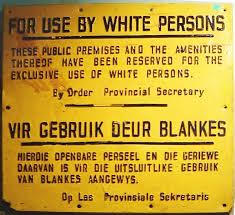

Thapelo’s family is one of the 40-plus million victims of South Africa’s apartheid. In 1948 the all-white National Party in South Africa gained power enacting laws of segregation, which created a horrific system of genocide, torture, and repression known as Apartheid. The Apartheid laws allowed for the total rejection of the largest segment of its population, the non-white South Africans people—the Bantu (black), Coloured (mixed), and Asian (Indian and Pakistan). According to history.com, between 1961 and 1994, the perpetrators of the National Party forcibly removed more than 3.5 million people from their home and deposited them in the Bantustans, ghettoes also known as homelands or black states, which were developed in 1959. The Bantustans comprised of 13% of the land for approximately 75% of the population.

Those who outwardly opposed and resisted apartheid were severely punished, killed, or forced to exile. Those in exile told the world what was going on in South Africa, which prompted an uprising among the international community. For 50 years, despite international pressure, black South Africans were forced to live a life of poverty in places like Thapelo’s hometown, Winterveldt. It was not until 1991 when President F.W. de Klerk began to undo the Apartheid laws. By then, the victims who survived the Apartheid system suffered physically, emotionally, financially, and intellectually, unable to enjoy the ending of apartheid and the freedom the law would allow them.

Because the Apartheid greatly limited freedom of expression and speech, musicians and artists were strongly repressed. Anne Schumann wrote in an essay, “Musicians ‘of color’ in South Africa were denied opportunities to make a living performing their music during the Apartheid.” Musicians played, despite the imposed restrictions, “initially starting as a mirror reflecting the popular experience, however as time went on and resistance movements started to emerge, music and creative expression started to become a hammer with which to ‘shape reality’,” Schumann explained.

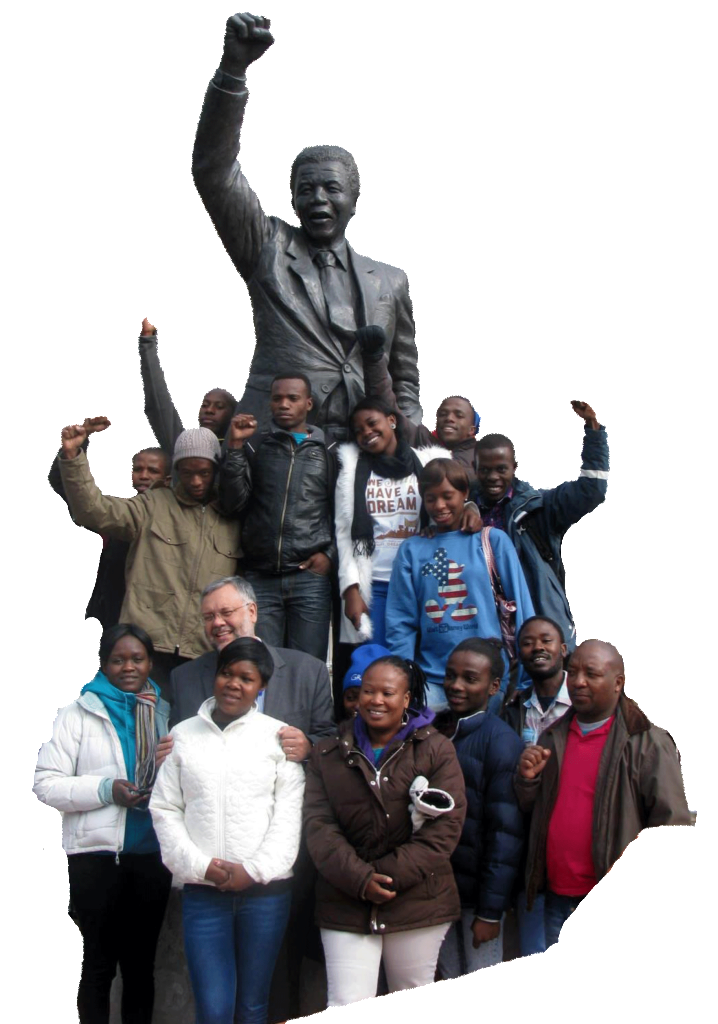

Two world-renowned musicians are icons of the Apartheid. The flugelhorn, trumpet, and cornet player Hugh Masekela chose exile, leaving his homeland in 1961 for the United States, sharing the stories of the Apartheid. His music inspired Bob Marley and Jimi Hendrix. He collaborated with Paul Simon, producing “Graceland.” His song “Bring Him Back Home,” was an anthem for the release of Nelson Mandela from prison. Thirty years after his exile, Masekela returned to South Africa. The all-male choral group Ladysmith Black Mambazo emerged in 1970, performing music in South Africa that combined traditional South African mine music called “isicathamiya” and acapella called “mbub”. After apartheid was abolished and Nelson Mandela was released from prison in 1993 they released the album “Liph Iqiniso,” which included the song “Liph Iqiniso,” meaning “Freedom Has Arrived”. In 1994 Mambazo sang when Mandela received the Nobel Peace Prize and at Mandela’s inauguration in 1994.

Thapelo was born in 1985, the year Americans Steven Van Sandt and producer Arthur Baker founded the Artists United Against Apartheid. Van Sandt and Baker brought together a group of influential musicians including Bob Dylan, Herbie Hancock, Ringo Starr, Lou Reed, Bonnie Raitt, Pat Benatar to sing “Sun City” and create an album by the same name. All of the participating musicians refused to perform at the Sun City, a resort located in the Bantustan of Bophuthatswana. This protest music opened up awareness in the west about the Apartheid and was banned in South Africa.

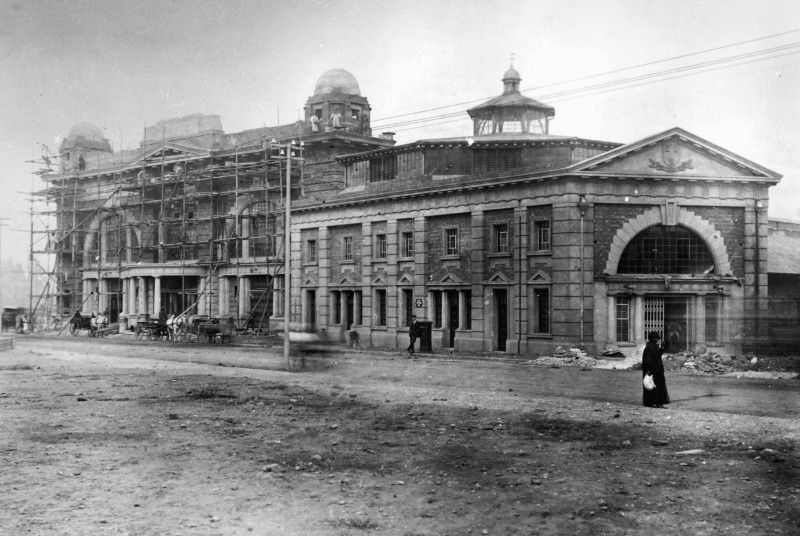

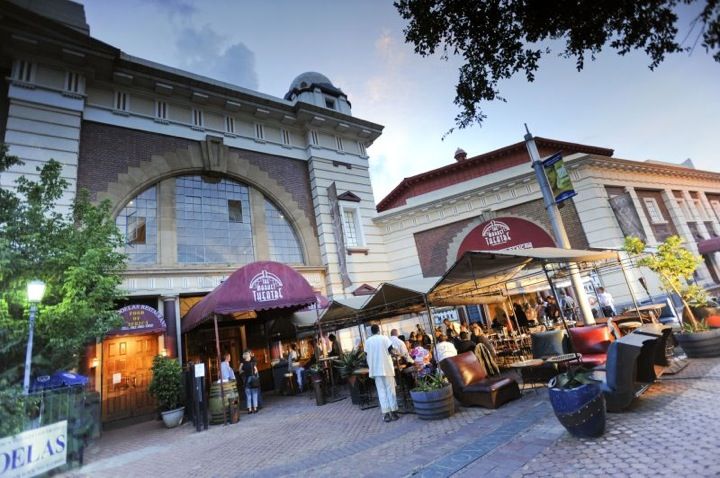

When the National Party started efforts to repress all non-whites, live theatre emerged as a voice for the repressed. Theatrical groups toured the country’s homelands, bringing plays to the people who were otherwise devoid of any entertainment or knowledge of events outside of their community. Plays like “The Kimberley Train, “Try for White”, and “A Kakamas Greek” told stories about the government’s apartheid system. In 1976 a group of theatre artists organized, raised funds, restored the dilapidated building in Johannesburg that once housed the old produce market on Margaret Mcingana Street, and opened the Market Theatre (above). The Market Theatre is internationally known as South Africa’s “Theatre of the Struggle”. The theatre’s founders Mannie Manim and Barney Simon believed that “culture can change society”. The theatre took on the Apartheid, providing a voice for the voiceless by producing plays that reflected artistic, social, and political freedom. Their first production was Anton Chekov’s “The Seagull”. Four months later they began staging other plays such as “Woza Albert!” about political resistance, written by Percy Mtwa, Mbongeni Ngema, and Barney Simon; “Asinamali!” about police violence, forced separations from families, and racist laws, written by Mbongeni Ngema; “Bopha!” about an activist son and his policeman father working for the oppressors written by Percy Mtwa (Morgan Freeman directed a film by the same name, which is based on this play); and “You Strike the Woman You Strike a Rock”. In the 1980s, the Market Theatre was one of the few places where black and white people could be together. Today, the theatre encourages the post-apartheid generation of artists to write plays that help South Africans “understand, interpret and thrive in the second decade of the country’s new democratic life.”

In 1999, South African Steven and Mary Anne Carpenter, a doctor and nurse, founded the Bokomosa Youth Centre, part of the Bokomosa Youth Foundation. Bokomosa, which means “future” in Tswana, supports at-risk youth. Under the direction of Mmule Tsaoi, Bokamosa is healing the remnants of Winterveldt’s ghetto, where the community struggles with issues including a high unemployment rate (over 50%), a high HIV/AIDS infection rage (affecting 25% of the population), teen pregnancy, domestic violence and rape. Bokomosa’s programs include teaching life skills; raising awareness about issues associated to life of poverty, crime and unemployment; funding a scholarship program; running a performing arts program; providing counseling and social services, youth leadership projects and team-building, professional training, and skill building. Through such efforts, the Youth Centre is improving the quality of life for each individual in the program, which collectively improves their community’s quality of life.

Thapelo works hard to help his community’s post-Apartheid’s revitalization. Graduating from its youth program, Thapelo became a youth mentor and facilitator at Bokomosa in 2005. Studying acting and directing, Thapelo is an accomplished drama director as well as musician, becoming Bokamosa’s drama and music director in 2011. Drawing from the tradition of the Market Theatre, the Bokamosa Youth Centre produce plays about the post-Apartheid issues they face and the efforts of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission to restore justice.

While they perform in their community and in the towns around South Africa, Bokamosa also bring their stories in the United States. On February 6 and 7, 2015, Thapelo and members of the Bokamosa Youth Centre participated in a benefit performance for The South Africa Project 12th Anniversary in Washington, DC. Produced by The George Washington University’s Department of Theatre and Dance, the group performed two acts that included the song “Sanibonani”; “The Truth Shall Set Us free”, a play and music written by Thapelo, “Tribute to Bra Solly”, poetry and song by Roy Barber, Leslie Jacobson, and the youth of Bokamoso; and “Going Back to My Roots”. Thapelo and Bokomosa have also performed in communities in Washington, DC’s Anacostia and in Philadelphia where he says at-risk youth issues are similar to those in Winderveldt.