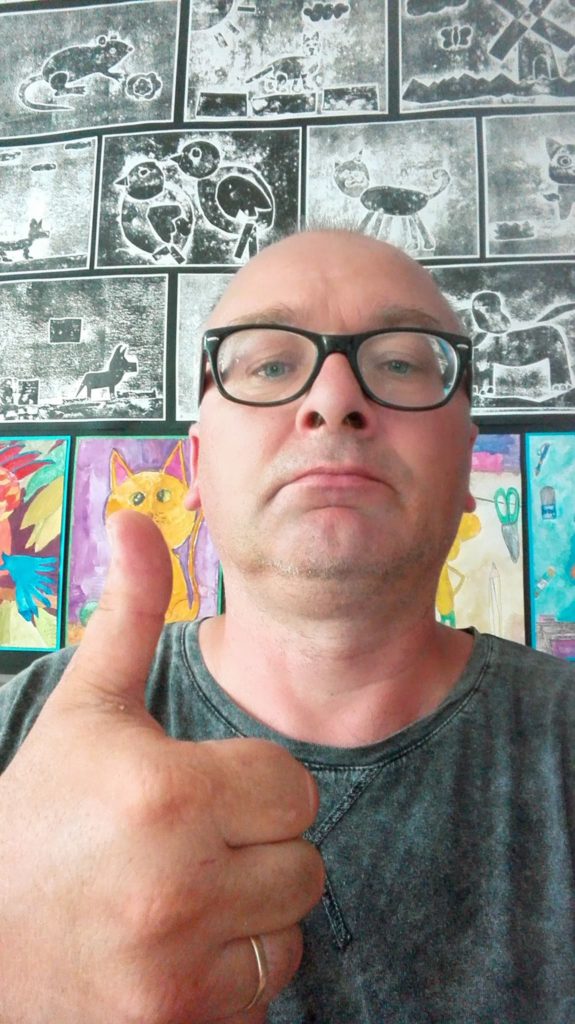

Maciej Frankiewicz

Visual Artist

While traveling in Poland with Classrooms Without Borders, an organization that leads educators and students on tours about Jewish history and culture, we discovered an unexpected treasure. Displayed in the lobby of the Kino Miejskie theatre in Starachowice was the artwork of Maciej (pronounced Macie) Frankiewicz, a Polish painter whose life work is to tell the story of the Jews who once thrived in the town where he was born decades later.

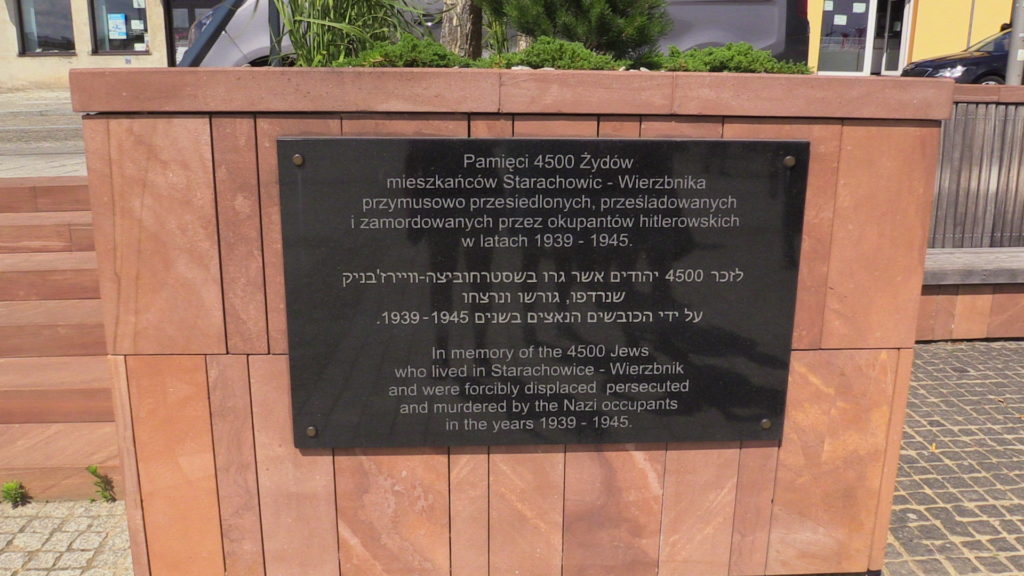

Born in 1968 to a Catholic family, Maciej grew up in Starachowice in Kielce county. Before World War II, Starachowice was at a shtetl called Wierzbnik where a large Jewish population lived until the Nazis came and wiped them out, sending the innocent people to the Warsaw Ghetto then, for many, later to their deaths at Treblinka.

And this is where the remarkable story begins. A Gentile devoted to preserving the memory of Jews who were exterminated during World War II.

Maciej works in the Jewish cemetery in Starachowice, which holds a great deal of history, but little personal stories about those who are buried there. He wanted to know more about these people whose remains he tended. In response to this void, Maciej set out to learn about the Jews who once were the majority of the population in his town. He pored over archival material, collected artifacts, and began telling visual stories.

According to the International Jewish Cemetery Project, the unmarked cemetery, located on a hillside off of a public road, was established in 1891 with the last burials sometime between 1942 and 1944. Records indicate in 1921, 2150 Jews lived in the town, about 40% of the population. Once densely situated on 4 hectares of land, hundreds of gravestones, mostly engraved in Yiddish and Hebrew, and large unmarked mass graves dating back to the late 19th and 20th centuries have disappeared over time. Houses were built on the land, unearthing bones. During World War II, the cemetery was vandalized and for years there was no maintenance, protection, or care of the site. In an effort to protect the site, in the 1990s the cemetery was fenced in, but all that was contained inside was left in disrepair. Until Maciej came along. Working on his own, Maciej restored the toppled tombstones to their original upright positions. In 2001, his wife Anita and he established the Chamber of Jewish Remembrance in the Starachowice Cultural Center inside the Kino Miejskie theatre. In 2014, Szewach Weiss, the Israeli Ambassador in Poland, recognized Maciej’s work in the preservation of the Jewish Heritage, awarding him a special certificate issued each year to Poles.

According to Krzysztof Bielawski who wrote about Maciej in the Virtual Shtetl, not all people in Starachowice embrace Maciej’s efforts, after all, he is not a Jew. Some mockingly call him the “Chief Rabbi of Starachowice” and others disparage the names of his wife Anita and his 12 children, all names in the Old Testament. Yet Maciej has been unswayed.

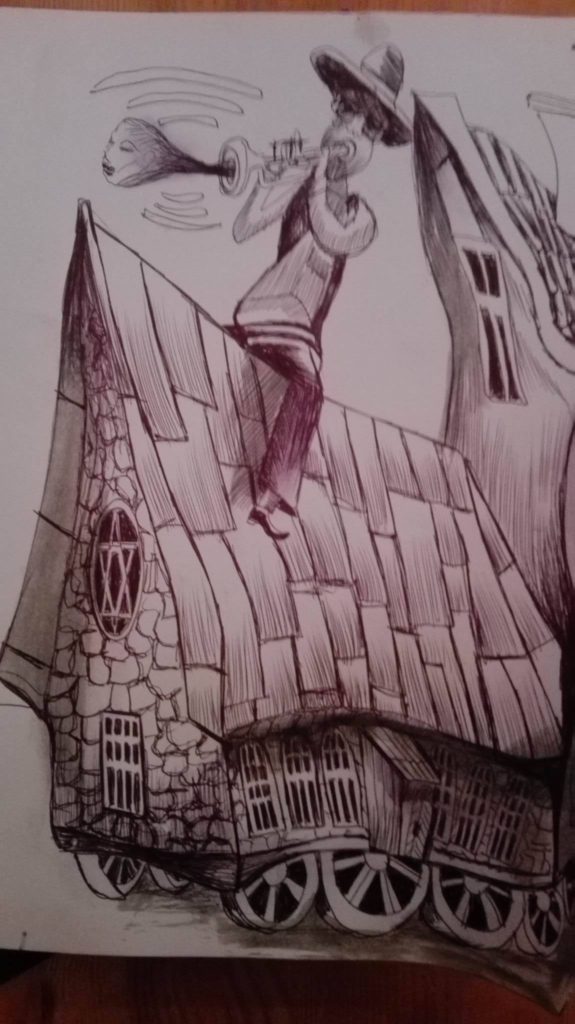

While he is not an academically trained artist or scholar, Maciej’s body of work is formidable. His paintings in tempera and oil pastel and ink drawings represent all that he has learned from the research he has conducted, preserving the memory of a Jewish life that thrived before the Nazis.

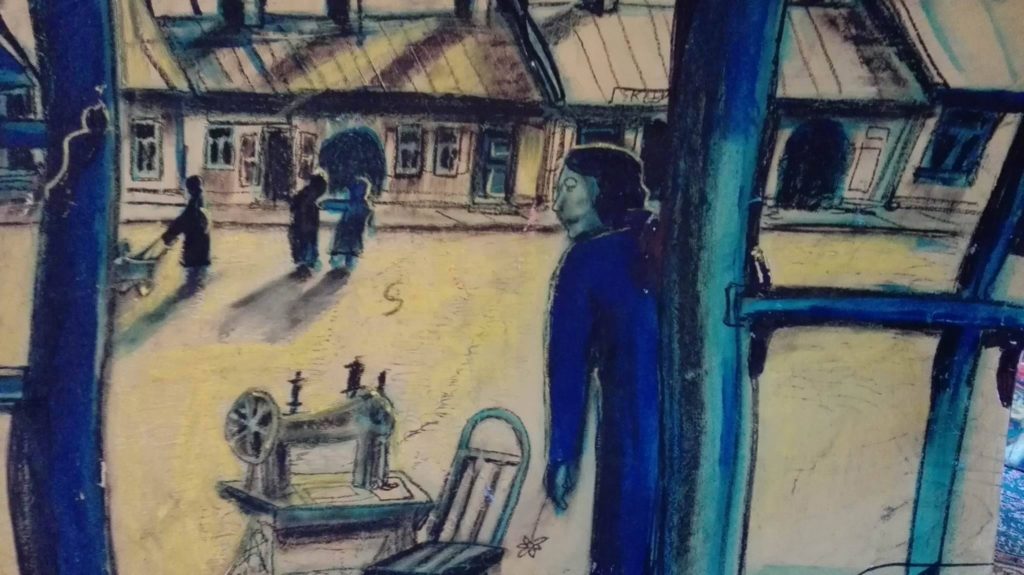

The painting (above) tells the story of the Starachowice-Wierzbrik Square. It is a day-in-the-life scene, allowing us to imagine life on a typical day in the shtetl. Below is the square as it appears today with houses from the time before WWII still standing.

Today a plaque is fixed on that square to commemorate the 4500 Jews who lived in the town and were forcibly displaced, persecuted, and murdered by the Nazis between 1939 and 1945.

Photographs and archival records feed Maciej’s imagination for his visual stories, as he describes in a few examples of his paintings, below.

Maciej’s work is exhibited in galleries in Israel and Toronto. He speaks to anyone wishing to learn about the Jews who once were the majority of inhabitants in his town, known decades ago as a schtetl called Wierzbnik.

Special thanks to Wiktor Kuptel for stepping in as interpreter during this interview with Maciej.