Asya Zlatina

Dancer and Choreographer

Asya is an exquisite force of nature and rising professional modern dancer. Having trained at the Kirov Academy, Dance Explosion, and the Washington School of Ballet, she graduated with a BA in dance and psychology from Goucher College in 2008. She received her MS in Administration from Drexel University in 2013, and teaches dance at Stockton University. After graduating, Asya joined the Koresh Dance Company. She lives in Philadelphia where she continues to dance with Koresh as well as teaches dance at Stockton University.

Her mother, Galina Teverovsky, is from Chechnya, located in southern Russia, near the Caspian Sea. For centuries, this region has endured unrest, in constant conflict with other Caucasian nations. Not until it became part of the Roman Empire in the mid-19th century, did Chechnya live in relative peace, which endured through its independence in 1917 until 1921 when it became part of the Soviet Union. Then in 1929, darkness swept over the Chechens, as it did for most Soviets when Joseph Stalin and his Politburo brought political repression and persecution to the USSR. One of Stalin’s early actions was moving people around the Soviet Union without giving them a choice of where they wanted to live. One of those shifts included moving ethnic Chechens and other Russians to Grozny, the capital of Chechnya.

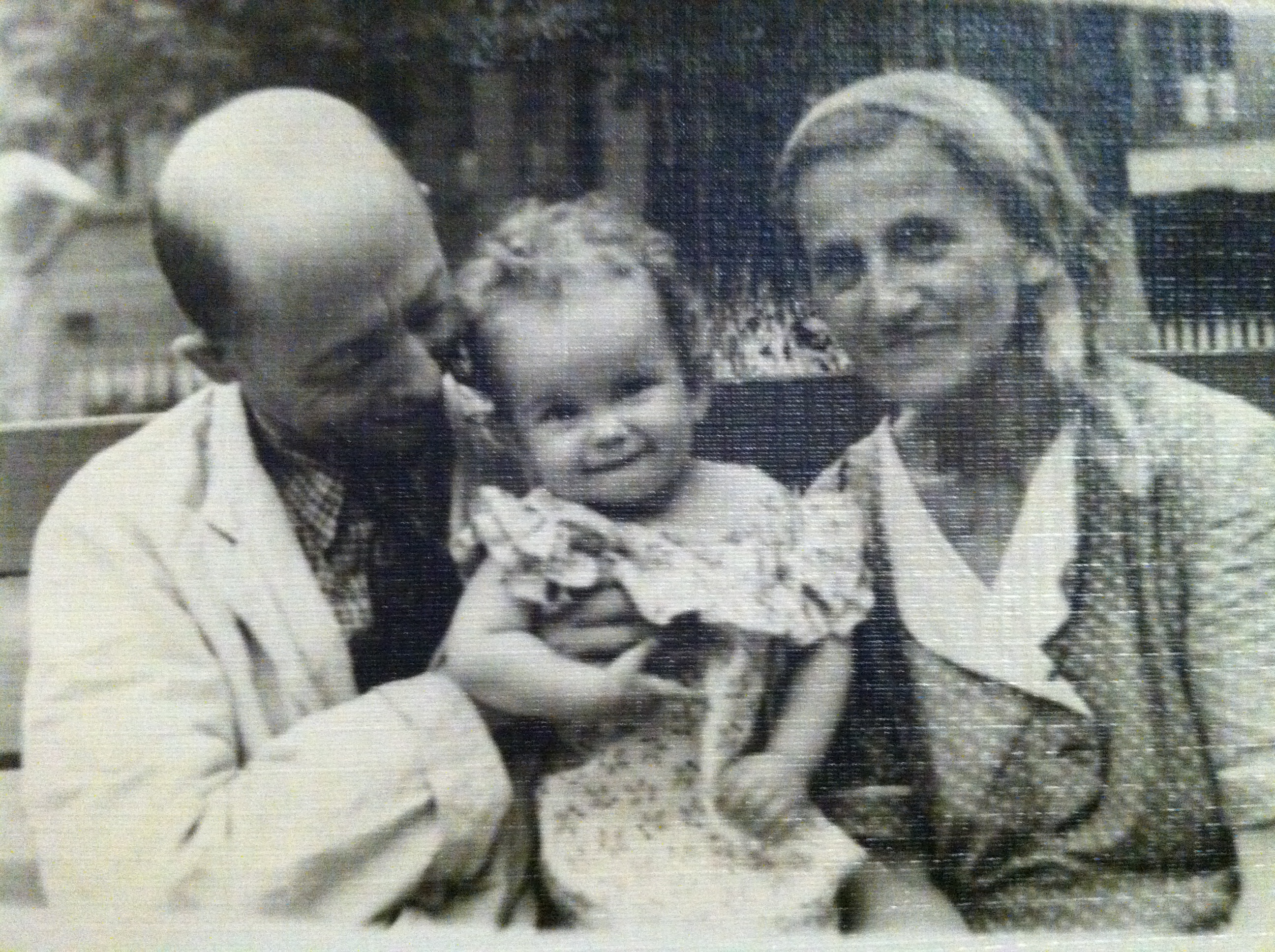

Ida and Israel Zlatin, Asya’s grandparents (above), were persecuted Jews and among those people who moved from the shtetls of Ukraine and Belarus to Grozny for a better life away from the anti-Semitic pogroms of eastern Europe. In Grozny, they raised their children, including Asya’s mother, Galina (below).

In 1987, when Galina Teverovsky, above, gave birth to her baby girl, the Soviet authorities told her that the name she chose for her newborn, Asya, was unacceptable. The name needed to be an official one, authorized by the Soviet Union. Determined to name her baby after her best friend, she named her Anastasiya because it contained the name As[i]ya. It was clear to the new mother that one day she would leave Russia with her daughter. She wanted to go to a country that would not lie to her, where people are free to name their babies, travel without restrictions, and be Jewish without persecution. That day came. A year after the Soviet Union fell, five year-old Asya and her mother came to the United States, settling in Silver Spring, Maryland.

When we asked Asya to describe what she knows about the freedoms of people today in Russia compared to the past Soviet concepts she said that today people are still not allowed to assemble publicly, but the authorities do not attempt to squash every public gathering. It is not unheard of that there is limited tolerance for protesting, political satirizing and criticizing in newspapers and television shows, which are very different from Soviet concepts. A dramatic shift in tolerance was reported on May 6, 2017 in the New York Times . “Pro-Western liberals, hardline nationalists, gay-rights activists and other Kremlin opponents gathered in central Moscow on Saturday, seeking to revive a broad-based protest movement against President Vladimir V. Putin that was snuffed out five years ago by mass arrests and stiff jail sentences. The demonstrators chanted the one demand that unites their disparate causes: ‘Russia Without Putin!’” Authorities approved the protest ahead of time. Police did not try to break up the gathering. It was reported that several thousand people joined the opposition rally. Though they had various political and social agendas (gay rights, socialists, nationalists, and critics of the government who plan to resettle hundreds of thousands of residents, to name a few), they came together in peace. The police reported no incidences.

Asya says that what has not changed in Russia since the fall of the Soviet Union is the mentality of the people. The conditioning of the old regime from Czarist Russia and the Soviet Union is still very present today. She believes that people like a strong hand, a forceful leader to keep a large country together. During the communist rule, there was no homelessness, there was no drug problems, there were jobs, and housing. Referring to the Jewish Torah, Asya recalls a passage where it describes that for some of the slaves who were taken out of Egypt, there was a moment when they wanted to return to slavery. It is a huge responsibility to take care of oneself and family. Freedom comes with a price. Many people in Russia are willing to pay this price, despite recognizing their country’s long and dark history. There is a resurgence of interest in Stalin. According to the LA Times in 2015, people are embracing Stalin’s “military command acumen and geopolitical prowess.” The article’s headline reads, “Putin, once critical of Stalin, now embraces Soviet dictator’s tactics.” People say that Stalin “kept us all together, there was a friendship of nation as, and without him everything fell apart.” “We need someone like him if we want peace and freedom from those fascists in Europe and America.” Asya finds this Stalin interest in Russia absolutely appalling.

Over the centuries, Russia has oppressed its people. Yet, at the same time, it has embraced and encouraged culture and the arts. Russian literature, philosophy, classical music, ballet, film, and architecture have influenced the cultural landscape worldwide. Before Asya and her mother left Russia for the United States, she started dancing and training in dance as soon as she could walk. By age 12, Asya discovered jazz and continued training in ballet. Then she started taking modern dance in college. In these classes, Asya could hear her inner voice and articulate it to the outside world through dance. Asya said that dance provides a multitude of ways to express something personal—her experiences from the past and meaningful issues she wishes to discuss—and at the same time give a platform to reach individual people that is a universal message.

While arts in Russia flourish, artists have been under intense scrutiny and unable to freely express themselves without severe repercussions. Deliberately and carefully, some artists choose, like Nikolai Khalezin and Natlia Koliada, to work underground in order to keep their art alive and spread their messages without drawing attention from the authorities. Khalezin and Koliada, exiled in London, England, founded the Belarus Free Theatre (BFT). The BFT is an example of an underground theatre company that is not recognized by the government and has no physical location or facilities. Called the executive arm of Ministry of Counterculture, an online platform to talk about the role that the arts play in social change, the Belarus Free Theatre produces, educates, and advocates about issues related to arts, international human rights, and social justice. They survive in exile and at home, despite the authorities’ harassment, performing secretly in private homes and outdoor locations, which change constantly, and on the Internet.

Not all artists take their art underground. Some defiantly confront the repression. Religious and pro-government activists were outspoken about their offense of the female punk rock group, Pussy Riot and the band’s unauthorized and provocative public performances expressing themes about feminism, LGBT rights, and their opposition to the authoritarian rule of Valdimir Putin. In 2012, the group performed inside Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Savior. The performance was considered sacrilegious to the Orthodox Church. The band members said they were protesting the Orthodox Church leaders’ support of Vladimir Putin’s election. On August 17, 2012, all three members were convicted of hooliganism motivated by religious hatred with a punishment of two years in prison. Samutsevich was freed on probation a couple of months later and her sentence was suspended. Alyokhin and Tolokonnikova served their sentences and were released in December 2013 after the State Duma approved their amnesty. Whether Pussy Riot is considered dissident art or political action using art, their call to action is not tolerated in Russia. No one can dispute that their artistic methods became a global sensation and necessary attention to the human rights issues and repression of creativity and expression in Russia.

Another example of artistic defiance confronts Russian law, banning and insulting state authorities and prohibits homosexual propaganda aimed at minors. In 2013, the Russian police removed, without documents authorizing the search or explanation, a print of the painting called “Wrestling” depicting Vladimir Putin and Barack Obama posing naked from the G-Spot Museum in St. Petersburg. Later the authorities shut down the museum. Then they raided the Museum of Power, taking away four paintings, including one of Putin and Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev wearing women’s lingerie. Shortly after the raid, Konstantin Altunin fled Russia, seeking asylum in France.

What would have happened to Asya if she remained in Russia? She would have likely pursued her dance career, but may not have discovered the freedom to express her passion in the way she does today. Still young in her career, Asya has time to develop the ideas, issues, and stories about which she care to express in dance.

Asya is in the process of creating several original works and has choreographed her first completed work. It is the first time she has created a dance where she can express her own voice instead of being a dancer for another artist’s voice. The dance is called “Barry: Mamaloshen in Dance!”, a tribute to the memory of Asya’s grandparents, Ida and Israel. It is a celebration of hope and survival, and a desire to hold onto her family roots, nearly extinguished. Asya explained that she is haunted by her past and the memory of her loving grandparents who experienced hardships such as anti-Semitism and pogroms. She wants to ensure that their existence is permanent.

The title “Barry” is a nod to the music Asya’s grandmother loved—the songs by the Yiddish Swing duo, Minnie and Clara Bagelman (also known at the Barry Sisters. “Barry” tells the story of Asya’s grandparents and Jewish life in the shtetls of Ukraine and Belarus in the early 20th century. The dance incorporates details of what Asya heard from her grandparents and certain things she knows about the small movements that are actually specific to Yiddish culture movements. Asya said, “This is how the Jews in the shetl danced!” They are familiar dances experienced at weddings and family occasions. “Barry” debuted in September 2016 at the Philadelphia Fringe Festival and was performed at the Kennedy Center’s Millennium Stage on April 5, 2018, which you can view here. Asya performed a new dance that she choreographed called “Storm”, which debuted at the Philadelphia Fringe Festival in September 2017.

The Jüdische Kulturbund Project, Asya believes, will impact people around the world, thanks to the availability of technology. People can easily access the stories and hear about others who are going through the same thing, be touched them, and feel hope. The stories are inspiring, they give perspective, and encourage people to consider what others are experiencing and see how they choose to respond.