Htein Lin

Visual and Performing Artist

Htein Lin (pronounced “Tane Lin”) was born in 1966 in Mezaligon, a village located in the northern Irrawaddy Delta in Burma where his father owned a sawmill. Htein Lin began painting as a boy, attended Rangoon University where he studied law, and supported himself as a comedian and actor. Htein Lin was a student revolutionary in exile in India and on the Chinese border from 1988 to 1992 and a political prisoner from 1998 until 2004.

In Burma more than 3,000 political prisoners were incarcerated between 1988 and 2012. They included monks, students, politicians, and lawyers. Many political prisoners were arrested for opposing the viewpoints of the government or for taking part in non-violent protests. Political prisoners underwent torture and solitary confinement. After their release, the military harassed the former prisoners for the purpose of discouraging them from participating in political activities. The authorities also tried to isolate the former prisoners as well as prevent them from working and going to school.

Htein Lin also suffered torture at the hands of fellow students at a rebel camp in the mountains near the China border in 1991-1992 when around 20 of them were executed or died as a result of torture. He survived seven months of manacled detention, and through his art and comedy helped others to survive and ultimately escape.

Burma had enjoyed relative prosperity until 1962 when a junta led by General Ne Win took power and introduced the “Burmese Way to Socialism.” He founded the Burma Socialist Programme Party (BSPP), which in 1964 was declared the only political party. Ne Win controlled political, social, and economic life. Students in particular were deeply affected.

In 1988 students’ hostility and contempt for the authorities came to a head, not least following the demonetization of many banknotes in 1987 which meant that family savings were wiped out. In March, while students from Rangoon Institute of Technology (RIT) were meeting at a local teashop, a fight broke out between teenagers. Authorities responded, making several arrests that included a prominent general’s son. On learning that the authorities released the general’s son, students protested and one RIT student, Maung Phone Maw, was killed. It was then that Htein Lin joined fellow university students in protest because the authorities did not investigate the death of their colleague. The protesters were expelled from the school and the authorities tightened their grip on demonstrations. Instead of retreating, the protesters organized and mobilized the masses. The effort is known as 1988’s “Democracy Spring.”

Unable to control the demonstrations and the public’s strong support, the government was weakened and fell. In the absence of an effective government, monks, elders, and students tried to maintain order, but failed. Chaos ensued. Prison riots resulted in thousands of criminals freed to the streets. Violence and lootings increased. Martial law was enforced and on September 18th, a new government body was installed under the name of the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC) led by its chairman and prime minister Saw Maung. While demonstrations and strikes continued, the military took measures to suppress demonstrations and killed thousands of unarmed protesters.

Aung San Suu Kyi, the daughter of General Aung San, Burma’s revolutionary hero, had entered into the political debate in late August and promised hope for the Burmese. However she was held under house arrest from 1989 until 1995 (and detained periodically thereafter). The SLORC changed Burma’s name to Myanmar in 1989, partially liberalised the economy, and promised an election and revision of the 1974 constitution. In May 1990, Myanmar held its first multiparty elections in 30 years. Despite her house arrest, Aung San Suu Kyi’s party, the National League for Democracy (NLD), won in a landslide victory, which the SLORC regime refused to acknowledge. Without international intervention, the SLORC remained in power. Saw Maung continued to lead the regime until 1992 when General Than Shwe him. A new constitution was adopted in 2008 and an election held in 2010, although neither were democratic. However since then, reforms in Burma have led to some loosening of controls on freedom of expression and a new parliament, under new president, Thein Sein as reported in The Economist.

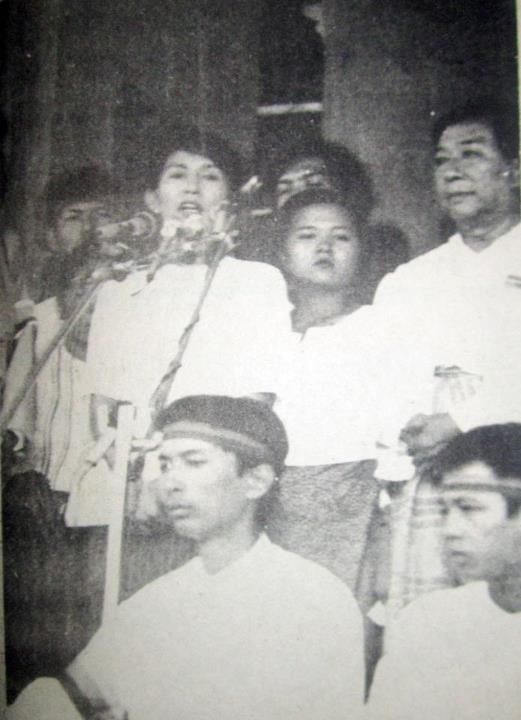

In 2010, the defiant Nobel peace-prize laureate (1991) Aung San Suu Kyi (above) was released from house arrest. Today her image appears in public, when only a few years before it was forbidden. Her NLD party, which was for decades deemed illegal, accused of rigging the 1990 election, is now legitimate and won over 40 parliamentary seats in byeelections in 2012, including for Aung San Suu Kyi herself. Most sanctions against Burma have been lifted, leading to an influx of Western companies like Coke, Visa, Unilever and Shell.

*****

After the SLORC takeover in 1988, Htein Lin went underground, spending time in a refugee camp near India where he studied art with Mandalay artist Sitt Nyein Aye. In 1991 to 1992, for about nine months, he was detained with other students in a rebel camp at Pajau near China where he sustained physical abuse by other students. Htein escaped the rebel camp, returning to Yangon in May 1992 to finish his law degree in 1995. He then worked as a comedian and actor, and held two solo art shows in 1996 and 1997. In 1998, he was arrested as a result of being named in letters written by former political comrades planning 10th anniversary protests, and spent nearly seven years in Insein (Yangon), Mandalay and Myaungmya prisons.

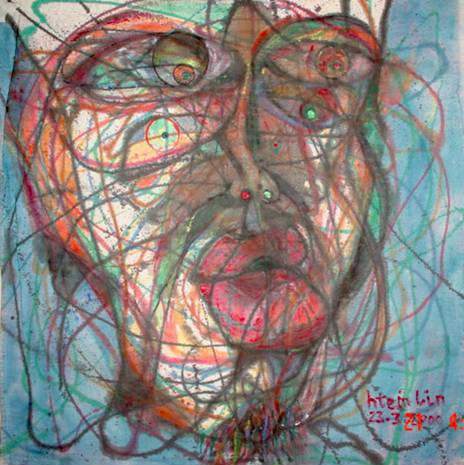

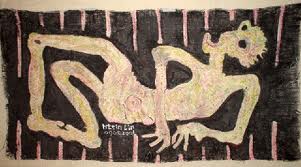

In Mandalay prison, Htein Lin continued his art even while confined, often in solitary. He took up meditation to cope. He persuaded guards with whom he became friendly to purchase and smuggle in paints for him. He used items in the prison like bowls, syringes, and cigarette lighters in the absence of brushes to make paintings and monoprints on the cotton prison uniform. Working at night and for two hours at a time while friendly guards were on duty, he used bars of soap to sculpt images of his cellmates and painted the prison surroundings and suffering faces of fellow prisoners. Above are self portraits, acrylic on cotton, May 2000 (top) and acrylic on cotton with syringe, March 23, 2000 (bottom). Htein Lin successfully arranged to smuggle more than 300 paintings and sculptures out of the prison, which were later deposited with the International Institute of Social History in Amsterdam.

Being a professional actor and comedian has provided him and others a lot of joy before, during, and after his incarceration. After his release in 2004, Htein Lin participated in a street performance called “Mobile Art Gallery/Mobile Market” in May 2005, resulting in five days of interrogation.

Life after prison for Htein Lin has dramatically changed personally and professionally. He left Burma for the first time in 2006 to live in England with his new wife, the former British Ambassador to Burma, Vicky Bowman. A year later, they had a baby, Aurora aka Ar Youn Lin. While living in England Htein experienced democracy and freedom of expression for the first time in his life.

Htein Lin has exhibited his art around the world and participated in events and projects to raise awareness about freedom of speech, especially in Burma. He contributes poetry, prose, and art criticism to Burmese language online and print magazines. In 2010, Htein Lin curated the first Burmese Arts Festival in London.

On December 12, 2012, Htein Lin was one of 80 artists from 24 countries who were invited and participated in the first annual Kochi-Muziris Biannale in India. Htein Lin’s multimedia art work titled “Special Court” was installed in Mandalqy Hall in the Jewish Quarter of Kochi. The installation was based on Htein Lin’s written story about his sentencing in the Mandalay prison.

In July 2013, Htein Lin returned with his family to live in Burma to take advantage of the new reforms in his country. He is currently working on “A Show of Hands,” capturing in plaster the hands of the thousands of former political prisoners in Burma. So far he has completed around 400. Htein Lin had the idea for this project when he broke his arm while living in London. It was then that he developed an interest in breaking, fixing, and healing. After he returned to Burma, he saw many of his friends, former political prisoners who were recently released from prison. While his friends are moving on with their lives professionally and personally, Htein Lin wanted to capture their experiences and make a record of their existence. He decided that because plaster of Paris is used to heal broken bones, it was the perfect medium for his idea. “A Show of Hands” is a multimedia work that uses text, photographs, and video, capturing the process of making the plastered sculptures of the hands and telling the story of the prisoners lives in jail and their lives in freedom. The “Show of Hands” represents how Burma was once broken and is now in the process of healing and is also about the process of engaging the community, performance, and public art.

Htein Lin’s art is collected around the world, including in the Artists Pension Trust, the US Embassy in Yangon, and private collections in Belgium, the Netherlands, Hong Kong, India, Singapore, Spain, Sweden, Thailand, the United States, and the United Kingdom.

A decade after he was freed, Htein Lin returned twice to Insein prison to supervise discipline at a 10-day meditation course on one occasion for prisoners and on another for nearly 100 guards. One of those taking the course was U Ko Ko Naing, one of his former guards. It seems that for most of us, we would avoid at all costs returning to the place of dark memories of torture and confinement. Not for Htein Lin. For him, he considers the prison the place where he did some of his best artwork. He also is grateful because being in prison allowed him to kick the habits of smoking cigarettes, drinking, and doing drugs. Perhaps this is an aspect of Htein Lin’s sense of humor?

While we experienced technical difficulties during our interview on Skype between Burma and Washington, DC, we were able to capture all of the audio and some video. Below we are sharing samples of one video and a couple of the audio-only segments.