Ammar Abdulhamid

Writer and Multimedia Artist living in the United States

Ammar was born in Damascus, Syria in 1966. When he was 17, Ammar studied English for three months in the United Kingdom. At 18, he spent a year at Moscow University before moving to Wisconsin in 1986. Two years later, he moved to Los Angeles, California, then returned to Wisconsin in 1990 to study history. He received a bachelor’s degree from the University of Wisconsin-Steven’s Point in 1992. In 1994, Ammar returned to Syria where he was a teacher in a school for children of diplomats and Syrian elites. By 1999, he started writing articles critical of Syrian President al-Assad’s regime and pushed for reforms. In the summer of 2005, he was profiled in the Arabic edition of Newsweek, described as having an impact on the status quo in Syria. Because of his anti-regime efforts, he exiled with his family to Silver Spring, Maryland in September 2005.

Raised as a Christian, Ammar discovered Buddhism at an early age. He embraced Islamic Fundamentalism in the mid-1980s only to reject it when he learned of the fatwah on Salman Rushdie. Then he discovered and took great interest reading the “Federalist Papers” while living in the United States. Since then, he has no religion, practicing emotional, spiritual, and psychological balance daily. He is prolific, writing blogs, poetry, novels, articles, and essays. He is human-rights activist, a television journalist, lecturer, philosopher and historian, commentator, and political advisor. He is also autistic (Asperger’s Syndrome), a husband, a father, and a son.

Ammar is deeply affected by his homeland’s history, culture, and extreme unrest. While Syria’s population is diverse, consisting of Kurds, Armenians, Assyrians, Christians, Druze, Alawite Shia and Arab Sunnis—it is a country intolerant of differences, which makes for great conflict. Since ancient times, Syria has bled from brutal invasions and occupations by the Romans and Mongols and later by the Crusaders and Turks. Today, Syria is tearing apart.

“When I was a boy, I had nightmares about Damascus. I would try and stop the destruction. Now, I’m living it.”

Three years before Ammar was born, Syria’s 8 March Revolution, also called the 1963 Syrian coup d’état, occurred. The military committee of the Arab Socialist Ba’ath Party successfully took over the government. Three years later, during the 1966 Syrian coup d’etat, the military committee led by Sala Jadid, overthrew and replaced the Arab Socialist Ba’ath Party. Jadid’s government was extreme and radical, driving a wedge between the Syrian and Iraqi branches of the Ba’ath Party. Many Ba’athists defected to Iraq. On November 13, 1970, another coup d’état occurred, which was called the Corrective Movement, led by Hafez al-Assad. Assad introduced reforms to strengthen the nationalist socialist state and party.

Assad has held his power over Syria for 45 years. His government has strictly controlled the populations’ freedom of expression, association, and assembly. Artists—writers, musicians, actors, dancers, and painters—have been continually censored and watched. Authorities are known to harass, arrest, and imprison human rights activists and critics of al-Assad. According to Human Rights Watch, Syria’s human rights record is among the worst in the world. Amnesty International says that during the 2011 uprising, the Syrian government committed war crimes involving a systematic enforcement of deaths during custody, torture, and arbitrary detention. Social media sites, such as FaceBook, YouTube, and Wikipedia were barred between 2008 and 2011. Today, media censorship is tight. Journalists and bloggers are often arrested, tried, and convicted. Internet cafes are required to record all comments made in chat forums.

Since 2011, after the “Arab Spring”, Syria has been fighting a civil war, often referred to as the Syrian Revolution. It began with nationwide protests against President al-Assad’s government, which resulted in authorities using violent force to control the protesters. Today, the conflict has grown larger and more violent, involving armed rebellions among various groups. Most prominent among these groups are the Free Syrian Army that organized in 2011 and the Islamic Front founded in 2013. Hezbollah joined the conflict in 2013 in support of the Syrian army. The Islamic State of Iraq and the Leant (ISIL) eventually entered Syria. They are a dominant force, fighting the other rebels and taking control of a third of Syria’s territory, including the country’s oil and gas production. The Syrian government has lost control of much of the country. Approximately 310,000 people have died in this conflict (as of April 2015). The United Nations have accused al-Assad’s government, ISIS, and other opposition groups of extreme human rights abuses and systematic massacres. Chemical weapons and bombs have killed many civilians. Thousands of protesters have been imprisoned and tortured. For the civilians, living conditions are poor and water and food is scarce. Over six million Syrians are homeless and more than four million have fled the country seeking refuge in other Middle East countries. After four years of war, the country is shattering, devolving.

The issues and conflicts in Syria are deeply ingrained in and troubling for Ammar. The issue of identity is evident. When he was growing up in Syria, in a sense, Ammar lived in two worlds: The outside world (Syrian society) was complicated and threatening and the inside world (his family’s home) was diverse and expressive. Syrian society, while predominately conservative, had an influx of political ideologies at play. There was the communist ideology; the social-national Arabic ideology; some liberal political ideas; and the Islamists whose presence were growing. Ammar’s family was dynamic. It’s members were Muslim, Christian, Arab-Kurdish, Jews, and Alawites. He traversed between the worlds. While attending school, he lived with his paternal grandmother in a very traditional Syrian society. When he was not in school he was with his parents, the theatre world, and high-arts community. He was distinguished at school because his accent was different from the other children. Being different created identity confusion for Ammar because in the outside world, society pushed homogeneity—diversity was wrong.

Ammar was nurtured in an open and expressive family of well-known performing artists in the Arab world. His father Muhammad Shahine (above, left) died in 2004. He was a famous scriptwriter, movie director, and head of the Syrian Foundation for Cinema. His mother Muna Wassef (above, right) is a film, television, and stage actress. Like many artists in Syria, they needed to navigate carefully through the regime’s repressive constraints and issues of censorship. For many Syrian artists, they never knew how far they could go in expressing themselves or the issues of the people. Many artists ended up siding with the regime out of fear. His mother was a rare exception. Sometimes she took on controversial roles. One such role was as an Israeli Jewish human-rights defender. For a Syrian woman to play this role in the 70s was unheard of. She was scrutinized and the authorities interrogated her. Eventually, because of her fame, the interrogations and harassments stopped. Shortly afterwards, and after starring in an international production about the life of Prophet Muhammad, directed by the late Syrian-American filmmaker, Mustafa Akkad, known to American audiences for his direction of the Halloween series, she was rehabilitated and celebrated again. In 2009, she received the country’s highest order of merit bestowed directly by Syria’s president, Bashar Al-Assad. Around that time, it was her son’s activities that were being condemned.

Ammar became an activist to try to stop his nightmare from coming true. He needed to speak about one of the major issues that he knew would play out—sectarianism and diversity. If Syria could not come to terms with these issues, it would destroy itself. It is difficult to describe all that Ammar has done in his activism—because he has done so much. His timeline from his birth in 1966 to today includes his writings—blogs, novels and poems; book publishing; being interrogated; protesting for human rights; starting the Tharwa Foundation; working as a fellow at the Saban Center for Middle East Policy at the Brookings Institution; meeting with Salman Rushdie; testifying before the U.S. Congress and again with the Human Rights Caucus; and moving back and forth between Syria and the United States.

Ammar has survived Syria’s wrath and watched his country’s decline, feeling powerless to stop the destruction. He and his family carry great loss in their survival. They mourn his wife Khawla’ Yusuf’s father, Abdulwadood Yusuf, a well-known scholar. In 1980 he was imprisoned where he died after being mercilessly tortured. After years of resistance and human rights efforts in Syria, Ammar, Khwala, and their two children fled their homeland to live in relative peace and safety in the United States. Ammar rarely sees his mother, now in her 70s, who chooses to stay in Syria, which causes him worry. His mother is afraid to visit Ammar because she is not sure Syria will allow her to return home. She wants to continue living in Syria where she still acts, providing some normalcy for herself and for audiences living in a country at war. In the United States Ammar and Khwala continue to raise awareness and fight for democracy and for the rights of minorities in Syria. But there is a cost for their choices. The regime has threatened their lives in the past and more recently ISIS has threatened them. His wife Khawla is on ISIS’s black list because of her work with the activists in Syria.

The torment of loss and memory of his experiences back in Syria lives in Ammar’s psyche and soul. He and his wife live with invisible wounds. To cope, Ammar searches for ways to articulate his nightmares and make sense of what he knows and has experienced. He never loses sight of his torment. Traversing a complex world between dark and light, between then and now, he slips in and out of high activity and dark idleness. Each of these cycles can last for years.

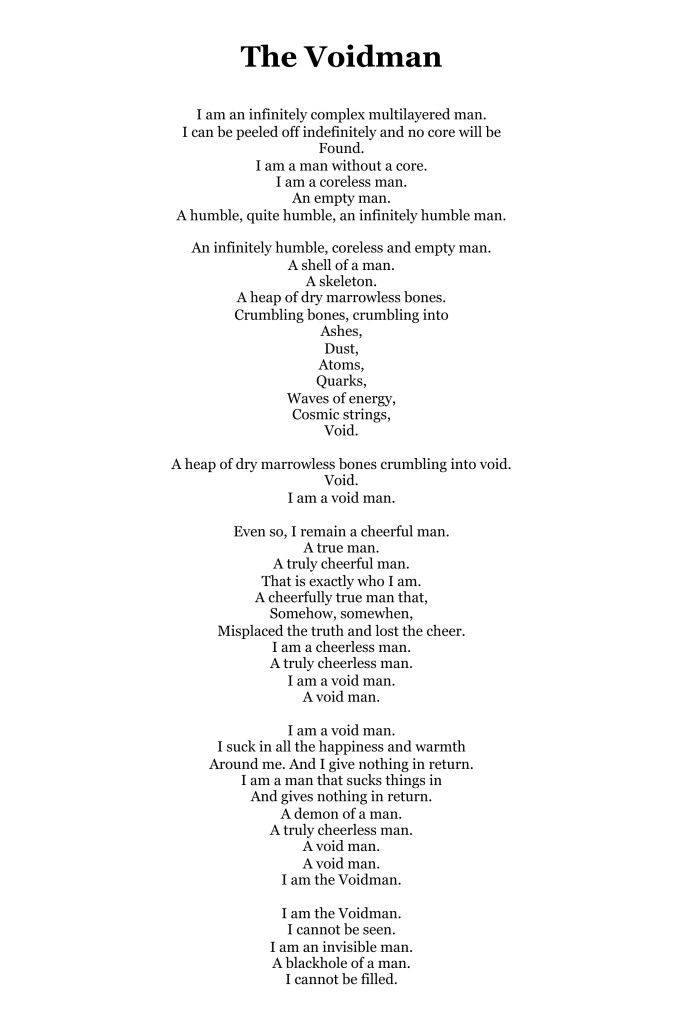

Among his early literary writings from the 1990s is his poem “The Voidman” written in 1993 (below). The poem describes the emptiness Ammar felt inside, which became one of a collection of poems also called “The Voidman”, published in 1997.

His unpublished novel “The Decent” is about an imaginary journey into the Netherworld, the place described by the Sumerians and Babylonians. In this story, Ammar meets the saints, the prophets and the holy figures. When he returned to Syria in the 1990s, he wrote social criticism about the realties he observed. In his poems, he wrote about Damascus and himself. Often the descriptions were woven together, making it unclear whether he was talking about the city or himself. Eventually started writing in Arabic as well as in English.

More recently, Ammar is cycling into a new phase of activity as a digital artist. The work reflects his personal experiences with the revolution. This included the time when he left Syria for the first time and imagined the plan for transitioning to a revolution, He was haunted by the concept of liberty and revolution. He also knew that revolutions are messy and they do not really fulfill anything beyond breaking the status quo. Ammar says revolutionaries destroy everything. Revolutionaries are wrong, but revolutions are usually right. He needs to explore these complexities and can no longer use words for this effort.

His concept for this ambitious digital work has been simmering for 10 years, but he struggled with how to realize it. In the last year, he has taken the Delecroix’s painting “Liberty Leading the People” and is digitally deconstructing it to express his commentary on all aspects of revolution, highlighting the dark aspects, civil war, violence, the burning, and the human tragedy. It is not a celebration of revolution as much as a dissection of the concept of revolution. Ammar thinks this digital art production might be his clearest response to all that he has witnessed and make sense of his nightmares. Above is a sample of this digital work called “For Liberty”.