Andrés San Millán, Theatre Artist

Stephanie Mercedes, Visual Artist

Emerson Eads

Musician

Machen Sie es, wie Sie wollen, machen Sie es nur schön.

(Do it as you like, just make it beautiful!)

–Johannes Brahms

We are opening up our hearts, hoping it is our time to face truth, reconciliation, and healing.

It is Winter 2021, and the world is in the middle, not the end of the COVID-19 pandemic. America has suffered racial unrest, an uprising in White Supremacy, a difficult presidential election, and domestic terrorism resulting in an insurrection.

Until last year, The Jüdische Kulturbund Project was not ready publicly to challenge America’s myth. The myth that believed it leads the world by its example: a country comprised of a unified, peaceful melting pot of multi-cultural people where equal rights are given to all who live here. The reality is far from this ideal and it is time to include America in the Project’s efforts to explore issues of oppression and response through music and art.

Where better to start this effort, but with the oppression inflicted on indigenous people of America?

Cindy C. Oxberry, The Jüdische Kulturbund Project’s Music Education Program Coordinator, thought immediately of Emerson Eads. Emerson grew up in Alaska and has a deep understanding and empathy for the Alaska Natives collective persecution. Currently living in Minot, North Dakota, Emerson serves as Director of Choral Activities at Minot State University. He is also a composer and conductor committed to creating music that is focused on social justice.

Emerson and Cindy met at the Fairbanks Music Festival in 2007 where she was the stage director of the festival’s opera program in which he participated. Growing up as a musician in Alaska, Cindy was sure that Emerson could help shine light on some of the issues we are exploring about how America has persecuted Alaska Natives.

Fortunately for us, Emerson was interested to participate, sharing his story as a musician and helping us understand the issues of Alaska Natives’ oppression. “When I was studying at the University of Alaska Fairbanks (UAF), I was made very much aware of the way that the native culture in Alaska was in some ways being kept as an artifact rather than seeing them as people, this rich tradition that they have and that lives, that is not dead,” Emerson explained.

Indigenous people of North America lived for thousands of years before the European settlers arrived in the 17th century. For many Americans, the indigenous people (also called “American Indians”) are seen in a romantic light. Thanks to tales told in books and in movies, many people think that the Indians are fine. They’ve been depicted as happy people living on reservations while preserving the traditions of their culture. We learned that Eskimos hunted for whales; Indians hunted and skinned animals to make their clothing from bear and deer. They traded furs and corn with the Europeans for gold. They were comfortable living in tepees and igloos. And we had fun playing cowboys and Indians. We even named sports team after them. That’s one kind of story we were told.

The other story we were conditioned to believe is that the Indians were the “other.” We were taught that they are ruthless savages who killed White people. They scalped their enemies and spread disease to European settlers. They were dangerous and needed to be separated from the gentrified folk.

The story of America’s indigenous people is far more complex than either of these simplistic perspectives.

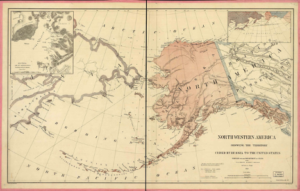

A map depicting the territory of Alaska in 1867, immediately after the Alaska Purchase.

Thousands of years before the arrival of the Europeans, indigenous people of Alaska cultivated a rich and diverse culture, comprised of nearly two dozen languages, histories, customs, and beliefs. They sustained themselves as skilled hunters, farmers, artisans, and healers. The first settlers to arrive in Alaska were from Russia in 1867. Welcoming their new friends, the indigenous people taught them skills needed to survive and thrive in their new settlements.

In 1867, the United States bought Alaska for $7.2 million. On May 12th, 1912, it became the 49th state of America.

Alaska holds the largest population of America’s indigenous people. Its indigenous population makes up over 15% of people living in Alaska. There are nearly 30 groups of Alaska Natives. Among them are Ancient Beringian, Holikachuk, Eyak, Tlinglit, Inuit, Eskimo, Aleut.

This mural, represents the distinct art style of the Tlingit (“People of the Tide”) who settled in the Southeast Alaska thousands of years ago, living among other indigenous people in the area. Half of the Tlingit population died of diseases, such as smallpox, after the Americans arrived in the mid 1800s. Later they would slowly lose their land to mining and logging companies.

For centuries, Alaska Natives and other indigenous people in the lower 48 have experienced broken treaties with the US government, faced discrimination that has resulted in short life expectancy, economic insecurity, violence, disease, malnutrition, loss of land, and illiteracy. Psychological repercussions of European’s persecution of Alaska Natives have resulted in a high percentage of suicide, drug addiction, and teenage pregnancy.

Emerson is the oldest of four brothers born six years apart: Evan, Eran, and Eric. Their parents, Emerson and Elaine, grew up together in a small town in California. After they married they moved to New Hampshire where Emerson junior was born. The young family uprooted for a new adventure, moving to Alaska when Emerson was six. In 1986 they moved to Alaska, America’s last frontier. When they arrived, they settled into a Christian community, where senior Emerson worked as the music minister and influenced Emerson to learn how to play the piano.

From an early age, Emerson set his sights on going to law school. But that idea changed when he attended Lael Hibshman’s choir class in high school. Lael graduated from Yale with a master’s degree in early music. Emerson wondered, how on earth did she find this place, 100 miles away from the nearest town. One day, Lael called on Emerson to conduct “For Unto Us A Child is Born.” Emerson thought, “No problem the class had been working on the piece.” Confident on his feet, standing before his choir class, hands in the air, he directed with ease. He was hooked. Lael invited Emerson to take private lessons to learn conducting techniques and pre-college music theory. If not for Lael and his father showing him the power of music, Emerson would likely have pursued a legal career to fight for social justice.

Young Emerson was the first to leave his family and the community to attend the University of Alaska Fairbanks. A few years later, Eran left to pursue his graduate studies in poetry at the Iowa’s Writers Workshop at University of Iowa. The brothers collaborate on projects, some of which we will share in this story. The rest of the family left the community a few years later, deciding to remain in Alaska.

Immersed in Christianity and music, Emerson’s embrace of verse and music comes naturally. As a young boy, he was sensitive, taking lessons to heart given from the ministry and various mentors, psalms, and poems. To this day, these lessons of love and concern for the oppressed are integrated in the music he composes. One of these inspirations comes from Pope Francis. Emerson shared two of Pope Francis’s text, written when he was a young seminarian, below.

I wish to believe in my history

(1:18 into the video, above)

Which was infused with the loving gaze of God,

Who crossed my path and invited me to follow.

To love without fear.

I believe I wish to love in abundance,

(4:00 into the video, above)

To love without fear,

To love in abundance,

To love without fear.

“I want my music to move people, I want it to be a place where they can reflect, empathize and heal.” Initially it was his composition teacher John Luther Adams’ environmental activism which made Emerson want to write and perform music with a connection to fighting oppression. This connection was cemented at the University of Notre Dame where the commitment to social justice is palpable. It was there under Professor Carmen-Helena Téllez and Professor Pierpaolo Polzonetti where Emerson was able to weld his desire for social justice and the two worlds of composing and conducting. It is in these shared worlds where Emerson seeks ways for his music to raise awareness about the oppressed, not just in Alaska, but around the world. He wants his music to allow the listeners the opportunity to share the pain that belongs to us all.

Several years after they met, Cindy told us that Emerson composed a Mass to shine a light on persecution and the oppression on Alaska Natives. Specifically, he wanted to pay tribute to Marvin Roberts, Kevin Pease, George Frese and Eugene Vent. They were four Native American teenagers in Alaska who were accused and sent to jail for 18 years for a crime they did not commit, the murder of 15-year-old John Hartman in 1997. They became known as the “Fairbanks Four.”

Imagine your worse day of your life. Now imagine living that day every day of your life. That’s what it feels like when you are innocent and in prison.

—Marvin Roberts, Fairbanks Four

Emerson explained, “I became aware of the story of the Fairbanks Four when I read a blog entry “Free the Fairbanks Four” by April Monroe, a journalist who was integral to their being released. She and journalism professor Brian Patrick O’Donoghue brought to light all the inconsistencies, lack of eye-witness accounts, and eventually even confessions by two incarcerated White men admitting to the crime.” As soon as the journalists revealed the facts of the case, the Alaska Innocence Project, jumped on board to represent the Fairbanks Four. Emerson believes that had it not been for these journalists, the Fairbanks Four may never have been released from jail.

Represented by William B. Oberly and founder of the Alaska Innocence Project, The Fairbanks Four were released in December 2015. As part of the terms of their agreement with the state they couldn’t seek reparations for the 18 years spent wrongfully in prison.

Emerson remembers reading a blog by April Monroe about Marvin Roberts being released from prison. Emerson said, “Marvin was interviewed shortly after being released and in a moment of candid grace, he relates how he went into prison with a 4 year old daughter, and left with a four year old granddaughter…the result of this harrowing 18 years wasn’t the rage you’d expect, but instead a healing bit of gratefulness for the love of his family.”

Reading this was not a feeling of rejoicing for Emerson. It was too deep, the time weighed heavily on his shoulders as he recognized that he was the same age of these men.

Emerson considered that from the time Marvin Roberts, Eugene Vent, Kevin Pease, and George Frese (above, left to right) were sent to jail in 1997 and released 18 years later, he has graduated from high school and was finishing up his graduate studies in music at University of Notre Dame. (Rachel Saylor, courtesy the Alaska Innocence Project)

After reading the blog, Emerson sat down that evening to write what he described as, “A prayer for peace, written to the lamb of god, to the person of god who is the meekest, the most gentle.” He set this prayer to music and the following day, brought it to his choral conducting professor at University of Notre Dame, Carmen-Helena Téllez. Professor Téllez. looked over the work and said, “This is not a one movement piece. This is horrible suffering. This needs to be a full mass.” At that moment the Mass for the Oppressed for mixed choir, orchestra and soloists was born.

“Mass for the Oppressed,” Emerson explained, “seeks to create an architecture where the ‘voice of the innocent’ can resonate with those who have suffered before them “until justice rolls down.”

Looking back, Emerson realized that no one said he couldn’t do this “Mass”. He just did it and along the way received support from many others, allowing him to premiere the “Mass” in Fairbanks. “Mass” was performed before a full house on July 30, 2016, including the Fairbanks Four. After the performance, Emerson greeted them (above). On the way out of the concert hall, Emerson asked Marvin, “Did you like the music?” Marvin replied, “Emerson, I didn’t understand a lot of it, but I liked it.” It is clear to Emerson that this “Mass” and the connection with Marvin and the other Fairbanks Four was such a transformational moment, so unexpected.

Since his graduate concert, “Mass for the Oppressed” has performed several concerts and has produced a recording, donating proceeds from the sale of CDs and downloads to the Alaska Innocence Project.

To give you an idea of the beauty and power of the “Mass”, Emerson shared a couple of excerpts and text with us.

“Mass for the Oppressed,” Performed on April 27, 2017 at the University of Notre Dame’s Concordia Choir and Ritornello Orchestra. Featuring Soprano, Tess Altiveros; mezzo-soprano, Toby Newman; Barry Banks, tenor, and bass-baritone, David Miller.

Emerson’s brother Evan’s poem is a part of the Mass, below.

They seek my name, I have no other.

Shall I be chained, am I a number?

I hold this hope small as a mustard seed,

That truth shall conquer and bound men freed.

This is my revenge:

I’ll dig on my knees in the deep earth until there grow trees!

(2:45 into the video, above)

After meeting Marvin’s mother and during his last year at the UAF, he also worked on he also worked on a cantata for the mothers of the oppressed. Emerson explained, “I took inspiration from Kahlil Gibran’s musings on the inseparable nature of joy and sorrow, that come from the same ‘well from which your laughter rises.’ The cantata uses text from the Bible and newly written poetry by my brother, Evan Eads (text below). This cantata is for mezzo- soprano, oboe, piano, chorus and strings. It features five movements, that draw inspiration from that one interaction with Hazel Roberts, mother of Marvin, one of the Fairbanks Four.”

“…from which your laughter rises,” a Cantata for the Mothers of the Oppressed by Emerson. The performance features Toby Newman, mezzo soprano and Thomas C. Moore, oboe. Performed at The University of Notre Dame’s Concordia Choir & Ritornello Orchestra on January 10, 2018.

I wish you the world and impossible dreams,

Rather hope and love than diamond rings,And a child’s heart that ever sings,

And a child’s hear that ever sings.I wish you love no prince can bring,

A love for poor downtrodden things,

And a child’s heart that ever sings,

And a child’s hear that ever sings.I wish you hope for broken wings,

Hands that hold, that hold,

Hold the crippled things,

The crippled things.I wish you the world and impossible dreams,

Lullaby, text by Evan Eads. Perfomed in the video, above)

Rather hope and love than diamond rings,

And a child’s heart that ever sings,

And a child’s hear that ever sings.

Before closing our interview, we asked Emerson how he might connect to the musicians in the Kulturbund and their response and resilience to the Nazis persecution on them. Emerson took a deep breath after hearing our question. He said that hearing stories about the Holocaust are difficult. To imagine what the Jews and Gays and all the people who were marginalized, it is hard to equate or relate to the horror in a meaningful way. But then he started talking about the recent COVID-19 pandemic. It forced people, musicians like Emerson, to come up with alternate ways of creating, educating, and performing in a virtual, digital world.

In the spring of 2020, The Jüdische Kulturbund started a FaceBook group called COVID-19: The Oppressor. The group invited it members from around the world to share examples of art and music they found on social media. Roy MacDonald, an early member of the group, offered to produce a music video called “We are the Champions,” a homage to those who sacrificed their lives to help the rest of us cope during the pandemic. Bringing together musicians from around the world, Cindy invited Emerson to participate and then introduced Roy to Emerson. Roy asked Emerson to transcribe the choral part into written form. It was then distributed to the participating musicians to record their own vocal line using the printed music.

Emerson said, “’We Are The Champions’ is an example of how people use art in response to oppression, not allowing it to subjugate.” Emerson, members of his Minot Chamber Choir, and twin 10-year-old nieces, contributed their voices to the project. In thinking about that collaboration, Emerson said he didn’t make the connection of COVID-19 being oppression until he worked on this music video project.

Since COVID hit about a year ago, Emerson’s Minot Chamber Choir have not been singing. He thought about the pandemic’s impact on the community and decided to create a contest. He called it “Life and Love in the Time of COVID.” Inviting high-school kids from North Dakota to write poems about how they are affected by the pandemic, Emerson said they wrote heartbreaking and beautiful poetry. What was clear to Emerson is with this oppressor, Covid-19 hits everyone.