Habib Shedadeh Hanna, Musician, Composer, and Musicologist

Avshi Weinstein

Violinmaker and Co-founder of Violins of Hope living in Turkey

Avshi Weinstein is a third-generation violinmaker, following in the footsteps of his grandfather and father, Moshe and Amnon. He also works with his father to oversee their organization Violins of Hope.

In December 2018, we had an opportunity to meet with Avshi and film an interview with him to learn about how his family’s violin business and Violins of Hope.

We first learned of Violins of Hope in 2012 when filmmaker Josh Aronson was researching information about the Jüdischer Kulturbund while developing his documentary film Orchestra of the Exiles. Josh was interested in including in his film material related to the Kulturbund musicians who were founding members of the Palestine Symphony Orchestra, which was founded in 1936 by Polish violinist Bronislaw Huberman. While working on his film in Israel, Josh became friends with Amnon Weinstein.

One day we received a call from Amnon, calling from his violin shop in Israel. After introducing himself, he told us that Josh had told him about The Jüdische Kulturbund Project and he wanted to tell us about Violins of Hope, a story that has since reached tens of thousands of people around the world.

Violins of Hope begins with the story of Moshe and Golda, Amnon’s parents.

Amnon learned how to repair and make violins from his father, Moshe, a violinist who lived in Vilnius, Latvia until he and his wife, Golda, fled to Palestine in 1938. Shortly after their arrival, Moshe opened a violin repair shop. When the war ended, Moshe and Golda learned that nearly 400 of their relatives were murdered in the Holocaust. Their sorrow was so deep they never talked about their family again. Amnon shared his story before an audience at the Maltz Museum on October 16, 2015.

Moshe’s shop became an unintentional shelter for unwanted German-made instruments.

Many of the founding members of the Palestine Symphony Orchestra (today’s Israeli Philharmonic) were musicians from Germany and Austria, bringing with them their very fine instruments. After the war, when people started to hear about the Nazi atrocities, Israel banned anything German. Even on the radio, they would not say the word Germany. Musicians brought their German-made instruments to Moshe’s shop, giving him a choice: you buy my instrument or I’m going to break it to pieces. While Moshe suffered deeply from the hundreds of family members who perished in the Holocaust, he valued the musical instruments. He bought as many as he could. But no one would buy them—so they were worthless.

It wasn’t until the 1990s that someone took interest in the family’s violin collection.

A bow maker from Dresden started working in the violin shop and was curious about the violins and the people who played them. While growing up in East Germany, under Soviet control, the bow maker did not learn about the people who perished under the Nazis. There was no distinction among the Soviets who were killed during the war—they were not identified as Jews, Polish, or Roma. When the bow maker came to Israel, he met many Holocaust survivors and founding members of the Palestine Symphony. He convinced Amnon, after two and half years, to give a lecture about the violins and the people who played them to the Violin and Bow Maker Association in Dresden in 1999. Following the lecture, Amnon went on a radio program about the Holocaust, which also served as a way to help people locate their loved ones who were lost during the war. By the end of the program, Amnon asked if anyone had stories to share with him about people staying alive because of violins.

Where there were violins, there was hope.

—Amnon Weinstein

For two decades Amnon set out to restore his lost heritage, searching for violins played by Jewish musicians in the camps and ghettos during the Holocaust. By restoring the violins, Amnon believes “their voices and spirits live on through the violins”.

It is estimated that Amnon and Avshi have restored 72 instruments violins, violas, and cellos played by Jewish prisoners in concentration camps. Music saved many prisoners lives in the camps because their skill as musicians was useful to the Nazis. They performed before the Nazis officials and played to calm the prisoners into a false sense of security.

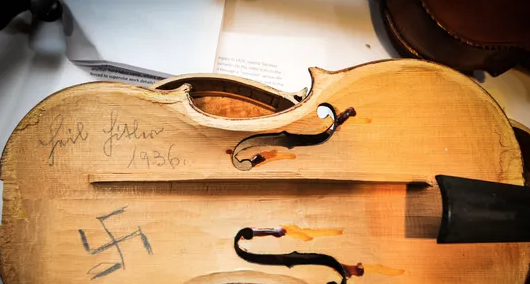

Many stories are told when an instrument is brought to the shop. Avshi told us about a violin brought to Amnon in the shop by a survivor of Auschwitz who wanted the instrument restored so his grandson could play it. When Amnon opened the violin, he saw black powder inside, the remains of ashes. Could it be that the violin was played on the way to the crematorium? Avshi is careful to say, there is no way to verify this or other story details. There are few records of such details left behind, other than what might be hidden inside an instrument, like the one shown above.

In 1999 Amnon founded an organization that works with orchestras that play violins from the family’s collection, performing symphonies in memory of the Holocaust. He named the organization Violins of Hope in 2008.

Avshi works with his father in overseeing Violins of Hope’s educational and multimedia programs. These programs are designed to illustrate the diversity of Jewish experiences during World War II and help others understand what happened in the Holocaust. Violins of Hope honors those who perished and provides hope for the future through the power of music, preserve the cultural identity of the Jews, and keep the memory alive for the Jewish artists who performed while trying to survive the Nazi’s efforts to annihilate them.

On September 27, 2015, Franz Elser-Möst conducted The Cleveland Orchestra and soloists Shlomo Mintz (violinist) and Thomas Hamson (baritone) in the opening performance of Violins of Hope Cleveland project (above). Before 1,000 guests in the audience, the orchestra played the violins from the Violins of Hope collection. This celebratory event was broadcast on PBS, streamed on the Internet, and aired on the radio.

The Maltz Museum outside of Cleveland, Ohio hosted the premiere of Violins of Hope: Strings of the Holocaust, a traveling exhibition on October 2015 until January 2016, which toured around the world. Violins of Hope was featured on the CBS Sunday Morning (December 2015) and PBS Newshour (and February 2016). A feature documentary film Violins of Hope: Strings of the Holocaust won an Emmy award and viewed at film festivals across the United States. The book Violins of Hope: Violins of the Holocaust, Instruments of Hope and Liberation in Mankind’s Darkest Hour, written by James A. Grymes in 2014, won a National Jewish Book Award that same year.

Below are excerpts of our interview with Avshi.

Hello,

I am the Programming Director for Jewish Federation of Grand Rapids, Michigan. I was wondering about Violins of Hope coming to our community. I tried to contact Amnon Weinstein at am*****@***il.com but that address is no longer working. I see the exhibit will be in Fort Wayne, IN in November of 2019 and we are a 3 hour car ride away from there. Could you give me a contact email for someone I could ask more questions to?

Thank you very much,

Marisa Krishef

Programming Director

Jewish Federation of Grand Rapids

Hello Marisa,

You can contact VOH on their Web site:

http://www.violinsofhopecle.org/contact-us/

Gail