Ultra-Orthodox Jewish women take part in a studio class at the Haredi branch of the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in Jerusalem on Dec. 8. (Heidi Levine for The Washington Post)

By Shira RubinJanuary 6, 2022 at 3:00 a.m. EST

The Washington Post

JERUSALEM — For years, ultra-Orthodox Jewish women in Israel have been on the leading edge of change inside their traditional, highly insular communities.

But they have recently been opening a new frontier, taking their quiet revolution to a nondescript building in a Jerusalem industrial area where, as students at an offshoot branchof a prominent art school, they are encountering both the secular world and fine arts in new ways.

Through their painting, drawing, photography and sculpture, these ultra-Orthodox women are revealing the interiors of their homes and communities to a new audience of secular teachers, while engaging in a form of creativity that has long had a controversial status in some Jewish traditions. The Ten Commandments prohibit making “a graven image, nor any manner of likeness, of any thing that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth.”

Some students paint abstract self-portraits, construct mazelike installations to simulate the frequently cramped homes of the ultra-Orthodox, or use their art to address topics such as mental health, considered taboo in much of their community. Many of the architecture students are drafting blueprints aimed at upgrading Israel’s growing ultra-Orthodox districts, where large families cram into small apartments and often lack access to public parks.

With the help of another student, Michal Rosenfield, right, a second-year art student and mother of three, shows one of her sketches during class. (Heidi Levine for The Washington Post)

With 220 students and growing every year, the experimental ultra-Orthodox wing of the vaunted Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design provides women with degrees in art, architecture and graphic design, which they are using to break into an Israeli culture scene centered in the mostly liberal and secular city of Tel Aviv.

For some of the women here, the intensive coursework and occasional 10-hour school days can complicate prospects for marriage, which the students say is all-important. Tehila Sasson, 21, a third-year art student, said she’s spent many of her recent arranged dates with men “explaining what art is, as a profession. There’s a lack of knowledge about it in the ultra-Orthodox world.”

Over the past decade, more ultra-Orthodox, or Haredi, women have married later, and many women who still marry by age 20 have been spacing out their pregnancies, leaving more time for their studies and careers, according to Lee Cahaner of the Israel Democracy Institute, who researches the ultra-Orthodox.

A photograph of Menachem Mendel Schneerson, leader of the Chabad-Lubavitch movement, on the desk of an art student. (Heidi Levine for The Washington Post)

Iris Ahuva Pykovsk works on her painting showing the Cave of the Patriarchs in Hebron, known to Jews as the Cave of Machpelah. (Heidi Levine for The Washington Post)

Their foray into secular, mainstream Israel has, by and large, been authorized by their rabbis, who praise the women for financially supporting their families — which average seven children — and enabling their husbands to study the Torah full time. The rabbis, however, also warn of its perils. “We may be winning the battle for our livelihoods, while losing the war for a home that supports the Torah,” ultra-Orthodox rabbi David Leibel said in a letter from a coalition of religious schools to Haredi families.

The director of Bezalel’s ultra-Orthodox branch, Rivka Vardi, a 45-year-old Haredi mother of eight and grandmother of three, said the new generation of Haredi women is searching for ways to ask questions and depict their lives, but also uphold their religious values.

The students continue to observe their traditions — praying three times a day, keeping a kosher communal kitchen, rocking napping newborns during lectures, and, if married, wearing wigs or head coverings in accordance with religious rules.

But there are also signs of rebellion. Lia Kalifa, 22, a first-year student from the ultra-Orthodox neighborhood of Sanhedria, has six tattoos, including on her ear and under her chin. Tattoos are widely viewed as a violation among religious Jews.

Lia Kalifa, 22, a first-year art student, shows her tattoos. (Heidi Levine for The Washington Post)

Kalifa said her photography walks a line between the permitted and the prohibited. She photographed the burning of a book she published, which had largely failed to sell, creating images that evoked the burning and desecration of Jewish holy books throughout history. Another work portrays ripped shekel bills, exploring the role of money in contemporary life — a subject that resonates in the Haredi context, with more than half the ultra-Orthodox population below the poverty line and many still deriding careers as “worldly” endeavors.

“Art,” she said, “is for the soul.”

Art remains a charged topic. Ultra-Orthodox rabbis instruct their followers to preserve tradition and social conformity, while modern art is often transgressive. Judaica stores sell decorative ritual pieces, such as menorahs, and hagiographic portraits of rabbis, but art as social critique is frowned upon.

Ahuva Weiss, a fourth-year art student and mother of eight, suggested that Jewish art has not developed in the same ways as Christian art for reasons that are historical, rather than religious. “The Jewish diaspora focused on surviving” and had few resources to devote to art, said Weiss. “At that time, we were only able to strengthen our legs, to run. But now it’s possible to create.”

Ahuva Weiss, 63, a fourth-year art student, heads out on a class exercise to search for objects for artistic inspiration. (Heidi Levine for The Washington Post)

Weiss stands before one of her creations made of fabric. (Heidi Levine/for The Washington Post)

Haredim make up about 12 percent of Israel’s population. They have long lived in separate enclaves, spoken Yiddish instead of Hebrew and shunned developments like the Internet and co-ed workplaces. But as their numbers surged and support from the Israeli government and Jewish philanthropies declined, ultra-Orthodox Israelis have been venturing outside their neighborhoods. At work and school, Haredi women — and, to a lesser extent, men — have been meeting secular Israelis, many for the first time.

Ousted from power, Israel’s ultra-Orthodox lose the final word on what’s kosher

Encounters between the ultra-Orthodox and the secular have reached new heights during the coronavirus pandemic. In 2020, 78 percent of Haredi women were in the workforce, many in Israel’s booming but understaffed tech sector, and more than 7,000 Haredi women entered higher-education programs, according to research by the Israel Democracy Institute (IDI). In both sectors, the rate for women was more than double the rate for Haredi men. The IDI study found that in 2020, 60 percent of Haredi families installed Internet in their homes, compared with 28 percent in 2009.

For the secular, the ultra-Orthodox are a source of fascination and have become a popular subgenre in the country’s television scene, with international hits like “Shtisel.” In turn, “there is a ‘Shtisel’ effect,” said Sheina Schechter, 25, a first-year art student, referring to the show’s protagonist, who paints while navigating the dramas unfolding in his Haredi neighborhood.

“That there’s a famous Israeli show that’s beautiful, has beautiful characters, who are learning about art — it started a conversation, that religious people can also be artists,” she said, adding that while she usually doesn’t watch television, she did watch “Shtisel.”

For Yael Mamon, 26, a second-year student, venturing outside her community and discussing subjects that are rarely broached there have made her look at her home with new eyes. “I would go to the place where I grew up and suddenly wonder, ‘What is this third-world country?’ ” she said. “But those are my roots.”

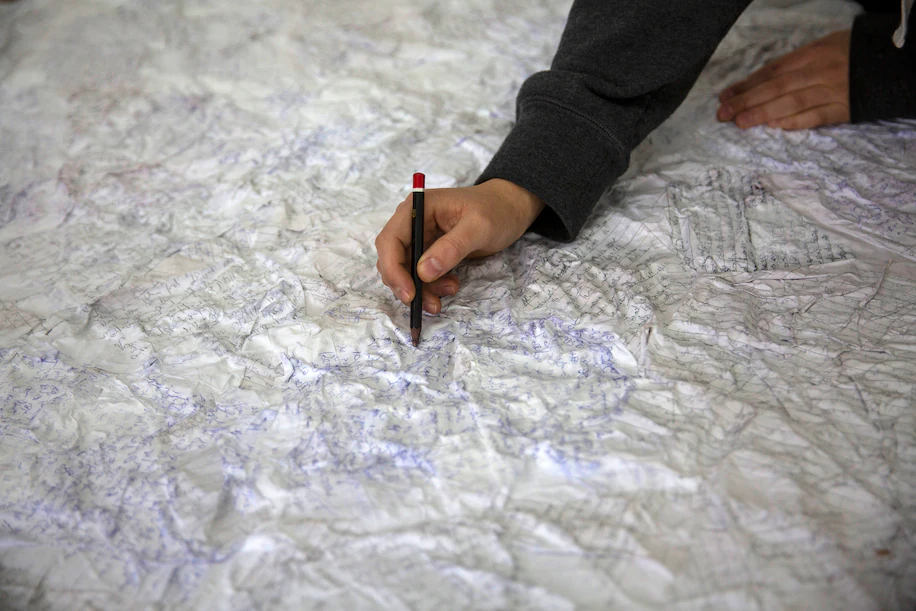

Yael Mamon uses pages of her handwritten diary to create a piece of art. (Heidi Levine for The Washington Post)

Even as studying art has opened her eyes, Mamon acknowledged that she has felt guilty for delaying marriage and a family.

Vardi began introducing art classes for the ultra-Orthodox two decades ago — first for children, then for their mothers and other women — in the working-class neighborhood of Romema. For seven years, she lobbied Israeli art institutions across the country to offer degrees to ultra-Orthodox women and eventually persuaded Bezalel to team up.

“I understand it: We have a lot of boundaries, and art is supposed to be without boundaries,” she said. “Though, I understand better now, everyone has boundaries.”

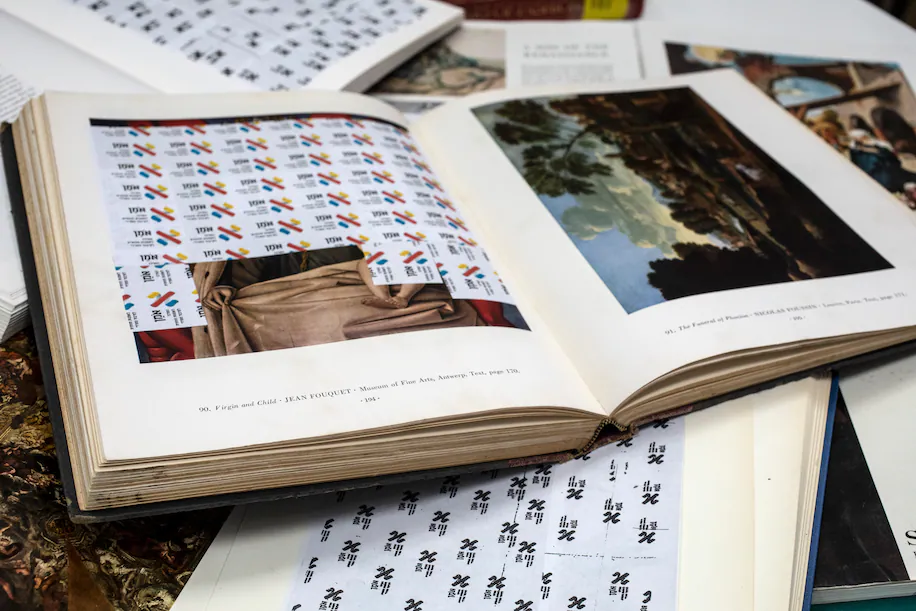

Leah Bezek, the school librarian, is tasked with censoring hundreds of art books from “excessive” references to Christianity and nudity — fundamental elements in most Western art-history curriculums. Bezek used white, branded decals to paper over Pablo Picasso’s seminal “Two Nudes,” though she left his “Demoiselles” painting, depicting five prostitutes in a steamy bordello. She covered Marc Chagall’s “The Violinist” — one of his paintings with the theme some believe inspired the musical “Fiddler on the Roof” — because of a cross in the background.

A few of the many art books that have been censored at the school. References to Christianity and nudity are covered with branded school decals. (Heidi Levine for The Washington Post)

Students can access some books considered borderline — depicting art, for instance, by Bruegel, Gauguin or El Greco — in a closed cabinet behind Bezek’s desk, and they can look up the censored art on their computers and phones. “My role is to give them a library that is kosher from a religious sense, but I’m not God,” she said, sighing.

“My hope is that a new generation of female Jewish artists can integrate modern art and Judaism,” Bezek said, and continue the debate on issues “I’ve only begun to contend with here.”