By Celeste Marcus

Ms. Marcus is writing a biography of Chaim Soutine.

Feb. 25, 2024

Pablo Picasso was among the few who stood beside Chaim Soutine’s grave as his corpse was lowered into it. It was Aug. 11, 1943, and Paris was under Nazi occupation. Mr. Soutine — the artist, the genius, the Jew — had died in his hospital bed with his belly cut open after being smuggled into the city in a black-and-white-flagged ambulance to avoid Nazi detection.

Mr. Soutine’s lover had insisted that he procure the best medical treatment available in France, despite the fact that they had been hiding together in the forests and farmland outside Paris so that he would not be rounded up and sent to an extermination camp. The hearse’s journey from farmland to hospital cost him precious hours. By the time the doctor performed the surgery, it was already too late.

At birth and death, the world assigned Mr. Soutine a status: He was born as a Jew — in a shtetl outside Minsk in what is now Belarus in 1893 — and he died as a Jew. In the 50-year interim he lived only as an artist.

Like many other Ashkenazi Jews, Mr. Soutine left Eastern Europe just after a spate of pogroms that rattled the Russian Empire in the 1910s. After studying painting in Minsk and Vilnius in present-day Lithuania, he joined the school of Jewish painters rankling the French art establishment in Montparnasse. His destitution was well known even in that impoverished milieu, but in the early 1920s an American art collector bought 52 of his paintings, catapulting him from obscurity into the annals of art history.

In the society of Jewish painters in Paris that he joined in 1913, Mr. Soutine was widely esteemed. He was monomaniacal: utterly, obsessively committed to his craft. “Soutine had no biography outside his art; one might even say that his art was a substitute for a biography,” one art critic wrote. On his deathbed, Amedeo Modigliani whispered to a dealer he and Mr. Soutine had worked with, “I leave you a genius. I leave you Chaim Soutine.”

Perhaps Mr. Soutine would have been surprised to hear that Picasso helped bury him (the two men shared friends but were not friends with each other), but I like to imagine I give his bones a greater shock when I say Kaddish, the Jewish mourning prayer, over his grave every time I visit its corner in Montparnasse Cemetery. Of the traditions he was bequeathed — the Jewish faith, Russian Jewish cultural heritage, the culture refugee communities cultivate in a cosmopolitan center — the only one he seized with both hands was the tradition of great artists in whose company he condignly placed himself. What does identity matter when one has been blessed with genius?

The story of his life can be told as a war between the force of his will and the force of history. History won when it reduced him to another victim of Hitler’s reign. Mr. Soutine’s story is universal and eternal.

Every generation births its own monsters with the same appetite to pulp a people’s will and to wring the artists from their art. Like Mr. Soutine, today’s refugees are members of a community of artists, broadly construed, who transcend circumstance, who seek out and seize and build their own identities in addition to the ones into which they were born.

“Every time I remember a book from my destroyed bookshelves, I weep,” the Palestinian poet Mosab Abu Toha recently wrote on social media. “It is more than paper.” In Gaza, his brother rooted through the rubble to salvage the books that hadn’t been destroyed. Art galleries throughout Europe have opened their doors to Ukrainian artists who are among the three million people displaced since the full-scale Russian invasion began two years ago. To live as an artist in exile is among the most glorious triumphs of human will: a spiritual victory.

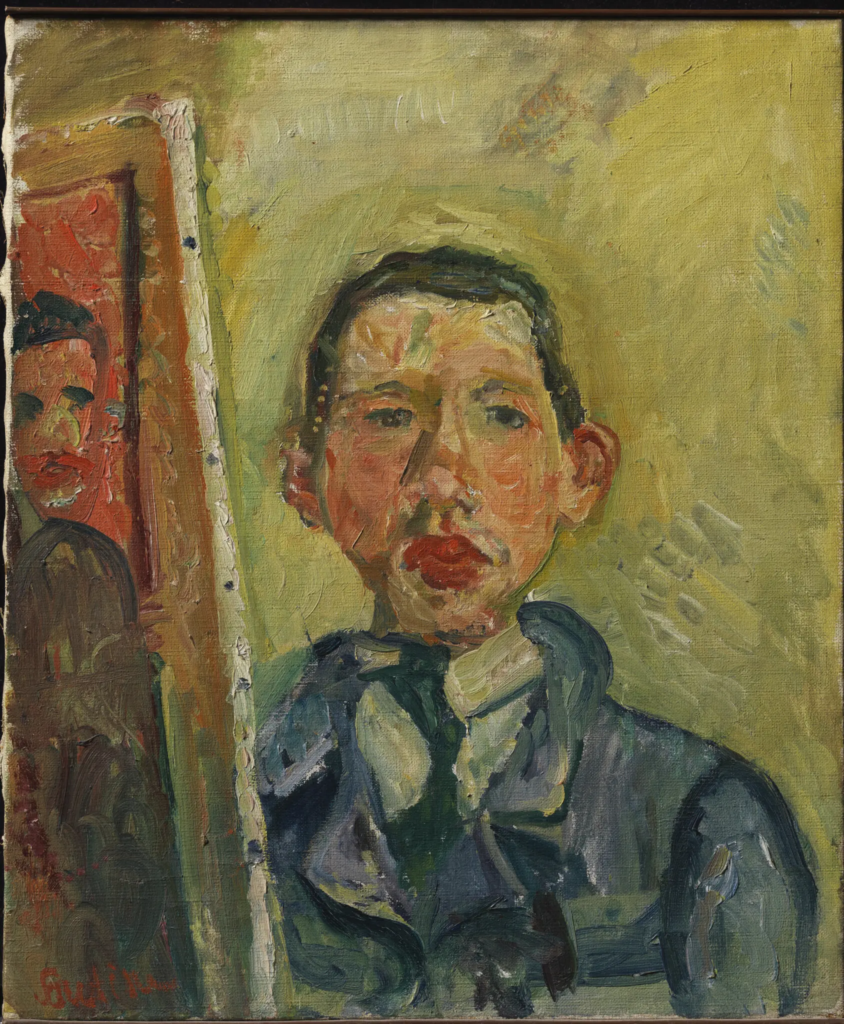

The majesty of Mr. Soutine’s work is the primary subject of “Chaim Soutine: Against the Current,” currently at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art near Copenhagen. It is the first major retrospective of the artist in over a decade anywhere in the world. The exhibit offers an overwhelming wealth of genius, the sum of five decades’ work. My favorites of his landscapes are the ones he did in hiding at the end of his life. The wind whips the trees in exhilarating blues and greens; he was home, which is to say he was himself, with a brush in his hand.

Mr. Soutine could not paint on command. He could only obey an inner necessity. To commence a work, he needed to feel possessed, overcome by the beauty of a subject and the bizarre compulsion to communicate that beauty in paint. He waited for these seizures of intelligent energy to grip him as a prophet awaits divine whispers. It is glorious to be a vessel for truth beyond ordinary comprehension. And if the compulsion — what he called “the miracle” — did not come, he would brood, growing increasingly anxious that the thunderbolt would never strike again.

His paintings look like the work of a man in the throes of something more than human. Élie Faure, the greatest art critic of the 1920s and 30s (with whom Mr. Soutine shared a brief and almost romantically intense friendship), said that Mr. Soutine was the most spiritual painter alive because he was the most carnal. For the “Boeuf Écorché” series that he painted in the 1920s, Mr. Soutine bought a full beef carcass from an abattoir near the artist colony where he once lived.

Mr. Soutine, entranced by Rembrandt’s “Slaughtered Ox,” wanted the color and complexity of the open body with its glimmering alizarin fibers and luscious tissues. When the meat began to decay and lose its flush, he bought buckets of blood and doused the beast to restore the precious red. Legend has it that his downstairs neighbors saw the sticky liquid leaking through the floorboards and began screaming, convinced someone had killed Mr. Soutine above their heads.

When neighbors forced open the door, they found him painting wildly, wholly immersed in his work. There was no distance between himself and his art. Art was his country. Art was his heart and mind.

“Culture,” said the Syrian artist Bashar, who fled Aleppo in 2015, “has no country, no language.” Bashar, Mosab Abu Toha and Chaim Soutine remind us that it is a blessing to be touched with the madness that compels us to create. Such people live in history but are not of it. They are more than pawns in the politics of their time: They are artists.