The first Pussy Riot retrospective reveals the Russian artists at their defiant best

Perspective by Sebastian Smee

Critic

The Washington Post

December 16, 2022 at 6:00 a.m. EST

REYKJAVIK, Iceland — For more than a decade, Pussy Riot — a feminist, anti-Putin art collective — has been staging brilliant, disruptive and often poetic political stunts. These “actions,” as the group calls them, have been part of its ongoing attempt to expose the absurdity and cruelty endemic in Vladimir Putin’s Russia.

For their efforts, Pussy Riot members have been subjected to government harassment, surveillance, beatings, detention, forced labor and now exile. They have also been championed by pop stars, including Madonna, and defended by human rights groups such asAmnesty International. They have been the subjects of documentaries, books and segments on “60 Minutes” and have graced the cover of Time magazine. All the while, as Pussy Riot’sfame has grown, their urgent warnings about Putin have come to seem increasingly prescient.

“Velvet Terrorism: Pussy Riot’s Russia” is the first overview of what Pussy Riot has been up to the past 10 years. Improvised, anarchic and viscerally intense, the exhibition — at Kling & Bang, an artist-run gallery on the Reykjavik waterfront — may just be the most important of 2022.

The first work you encounter as you enter the show is a short, sensationally provocative video. Filmed only days before the opening in the studio of Ragnar Kjartansson, Iceland’s most famous contemporary artist, the video shows Pussy Riot member Taso Pletner, in a red balaclava, standing on a table over a propped-up portrait of Putin. Pletner hikes up their black smock and proceeds to urinate on the portrait, before kicking it to the ground.

This is political art at its most courageous, least ambiguous and most devastatingly heartfelt.

When I arrived at Kling & Bang, it was 3 p.m. in Reykjavik, and the sun was already fading. In two hours, the doors would open. Among the expected guests would be Iceland’s prime minister, Katrín Jakobsdóttir. The first thing she and her entourage would see? The video of Pletner urinating on a portrait of … oh, just the nuclear-armed leader of a belligerent country not all that far from Iceland.

If this was going to be awkward for the prime minister, the show’s curators — Kjartansson, his wife, Ingibjörg Sigurjónsdóttir, and Dorothee Kirch — seemed unconcerned. This was Iceland. They were free. Besides, they counted the prime minister as a personal friend. In fact, earlier in the day, Jakobsdóttir and the visiting Finnish prime minister, Sanna Marin, had met with Pussy Riot’s Maria Alyokhina, one of Russia’s most famous dissidents, to discuss Ukraine.

Alyokhina, known to her friends as Masha, was now crouched on the gallery’s floor, writing text in black marker on the wall. Her friend Kjartansson was standing on a nearby stool, using silver masking tape to write a title. None of the screens were switched on. The digital file of one video was still missing (it was eventually uploaded two minutes before the opening). People scurried back and forth as the clock wound down.

Pussy Riot is used to flying by the seats of its pants. The group’s members improvise. They agitate. If they hit an impediment, they pivot and push in another direction. They all but define urgency. Although known to many as a punk band, they are best understood as artists working in the tradition of performance art. More specifically, they’re political performance artists.

Of course, there’s political art and there’s political art. The first kind preaches to the converted. It usually involves arcane allusions to the grievances of an identity group and rarely reaches an audience outside the art world. The other kind dares to engage in the actual political arena. It is oppositional, offering clear statements grounded in personal conviction. It understands, through bitter experience, what’s at stake. And yet it’s made with exuberance, an embrace of the absurd and antic, undaunted joy.

The idea of a Pussy Riot retrospective hadn’t occurred to Alyokhina until about six months ago. The 34-year-oldhas an astringent, understated charisma. An unlikely amalgam of Sid Vicious, Greta Thunberg and Harry Houdini, she has been resisting Putin’s regime with humor, smarts and an indefatigable brand of radical innocence for most of her adult life.

Kjartansson first suggested the idea of mounting a retrospective in December, 2021. When, the following May, he and Sigurjónsdóttir showed her Kling & Bang, Alyokhina had only just escaped Russia, where she had been living under so-called “restriction of freedom,” a kind of house arrest. She got out disguised as a food courier, with help from Kjartansson and an undisclosed European government.

“I was quite skeptical,” said Alyokhina, sitting in Kling & Bang’s back office two days after the opening. Pussy Riot, she explained, performed street actions; a retrospective might kill their spirit.

But the war in Ukraine had changed her outlook on everything. “We gradually understood that we don’t want to just show the videos [of Pussy Riot actions]. We wanted to tell the history behind the actions and to explain how we came to this point of war.”

A mash-up of order and anarchy

The action that first brought Pussy Riot to international attention was “Punk Prayer,” a 2012 guerilla-style performance of an anti-Putin song in Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Saviour. That chaotic, clumsily filmed 51-second eruption of indignation led to a show trial and convictions on charges of hooliganism motivated by religious hatred.Alyokhina and her friend Nadya Tolokonnikova spent two years in penal colonies. (A third participant, Yekaterina Samutsevich, was released after an appeal court hearing after eight months in jail.)

The retrospective traces the stages of Russia’s descent, in the wake of “Punk Prayer,” into state-sanctioned violence and authoritarianism. (“We didn’t receive all the hell in one moment,” Alyokhina told me. “There was a road that led to it.”) The show’s layout is a deliberate mash-up of order and anarchy.

After the video of Pletner urinating on Putin’s portrait, the show introduces audiences to each of Pussy Riot’s actions in the order they happened, beginning with 2011’s “Kropotkin Vodka,” which took aim at conspicuous consumption in the new Russia, and “Death to Prison, Freedom to Protest,” a punk-style performance on the roof of a building in front of a Moscow detention center holding political prisoners.

Text written directly onto the exhibition walls explains not only the actions, but also who did them, the context and the consequences. In a kind of conceptual jujitsu, Pussy Riot has successfully turned every arrest, detention and beating into new proofs of the absurdity of the authorities.

The show moves from “Punk Prayer” to “Putin Will Teach You How to Love the Motherland,” a series of actions (some of them thwarted) at the Sochi Winter Olympicsin 2014, just after Alyokhina and Tolokonnikova had been released from the penal colonies. During one action at Sochi, Pussy Riot members were attacked by Cossacks wielding whips. Another display revisits “World Cup: Policeman Enters the Game,” where several Pussy Riot protesters dressed as police ran onto the field during the 2018 World Cup final in Moscow between France and Croatia.

Sigurjónsdóttir, who designed the Kling & Bang exhibition, deliberately created a kind of labyrinth. “I wanted to make the space unfamiliar,” she said, so that audiences “lose the security that comes from familiarity.” The gallery windows have been blocked by opaque photographs, in one case of a surveillance car parked on the street below. Meanwhile, sounds from different videos clash and compete, generating a kind of punk energy rarely experienced in art museums.

Despite Pussy Riot’s abrasive, in-your-face audacity, many of its actions have a distilled, poetic, almost childlike quality. For “Paper Planes,” in 2018, Pussy Riot threw colorful paper planes at the building housing the Federal Security Service (FSB), Russia’s principal security agency, after Russia banned the Telegram app. For “Rainbow Diversion” (2020), an action framed as a gift to Putin on his 68th birthday, they placed rainbow flags on important government buildings around Moscow. And for “New Year Tree,” carried out on New Year’s Eve 2020, they decorated the Christmas tree outside the FSB building with 36 colorful, balloon-shaped ornaments decorated with portraits of political prisoners.

“I really think that if you do something in art,” Alyokhina said, “you should do it in a way to make all the people of different ages understand it. You should talk to people in a simple way. It doesn’t matter how complicated the thoughts are that you have inside. You should make it possible for people to understand.”

In her 2017 memoir“Riot Days,” Alyokhina wrote, “This is what protest should be — desperate, sudden and joyous.”

‘I don’t want to be silent’

In late 2021, before the invasion of Ukraine, Kjartansson was in Moscow for a survey exhibition of his performance-based works, the centerpiece of which was a live, ongoing reenactment of 98 episodes of “Santa Barbara,” the American soap opera that had captured the imagination of Russians after the fall of communism. Kjartansson’s show inaugurated GES-2 House of Culture, a gleaming contemporary art space in a former power plant across the Moscow River from the Kremlin.

In a curiously inverted foretelling of the Icelandic prime minister’s visit to the Pussy Riot opening, Putin had toured the new Moscow museum immediately before its launch. Several potentially controversial works were taken down to avoid incurring his displeasure.

On the suggestion of his friend, the photographer and journalist Misha Friedman, Kjartansson had invited Alyokhina to the Moscow opening. Over the previous year, she and her partner, Lucy Shtein, had been subjected to intensifying government harassment (Alyokhina was arrested six times) over social media posts calling for street protests in support of political prisoners, including opposition leader Alexei Navalny. In a spell between periods of house arrest, Alyokhina showed up at Kjartansson’s Moscow exhibition.

“That was the other state visit,” Kjartansson said with a laugh, telling his side of the story in the living room of the Reykjavik apartment he shares with Sigurjónsdóttir. He was amazed, he said, by Alyokhina’s fearlessness. “Masha was the only free person I met in Russia.”

When Kjartansson came back to Moscow in January 2022, it was clear to Alyokhina that war was imminent. Foreshadowing propaganda that the Russians would use against Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, the authorities had begun to cast her and Shtein (who, like Zelensky, is Jewish) as Nazi propagandists. When he saw that, Kjartansson remembers thinking,“‘Wow, these guys have a sense of humor. They’re hilarious.’ And then they invaded Ukraine.”

By now, said Alyokhina, the political police had started putting “signs on the doors of activists saying, ‘This is an enemy of the state’ or ‘collaborator.’ A sign like this, with a photo of Lucy, went on our door.”

Alyokhina realized that she needed to speak out against the war. “I wanted to write an antiwar song and, together with my collective, shout as loud as possible about what is going on. I don’t want to be silent.” She knew that she could do that only from outside Russia.

Getting out wasn’t easy. Her flat was surrounded by police. Her passport had been confiscated. She disguised herself in the green uniform of a food courier, left her phone behind as a decoy, and had a friend drive her to the border with Belarus, from where she hoped to cross into Lithuania. Two attempts failed. Vital assistance came from Kjartansson, who encouraged the officials of an undisclosed European country to issue a travel document giving Alyokhina essentially the same status as an E.U. citizen. The document was smuggled into Belarus and Alyokhina boarded a bus that took her to Lithuania.

European tour

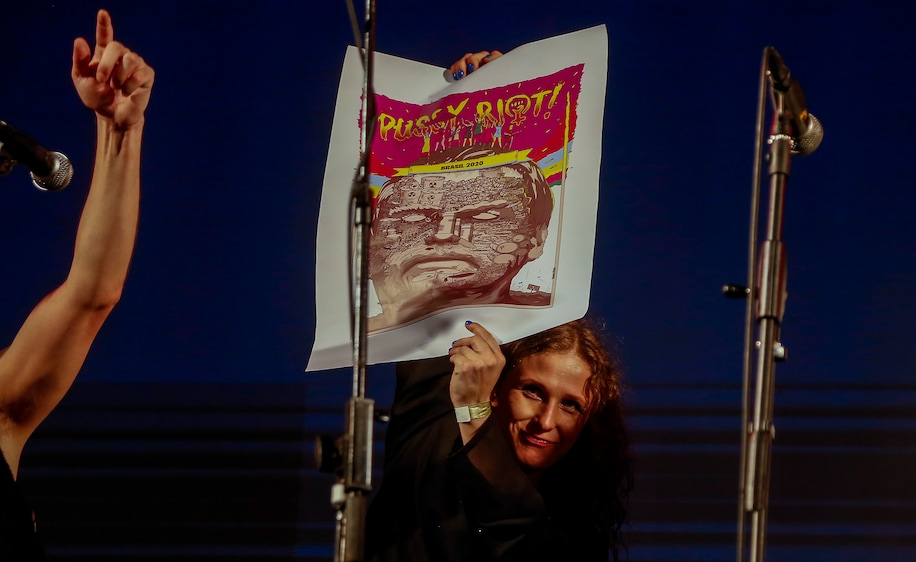

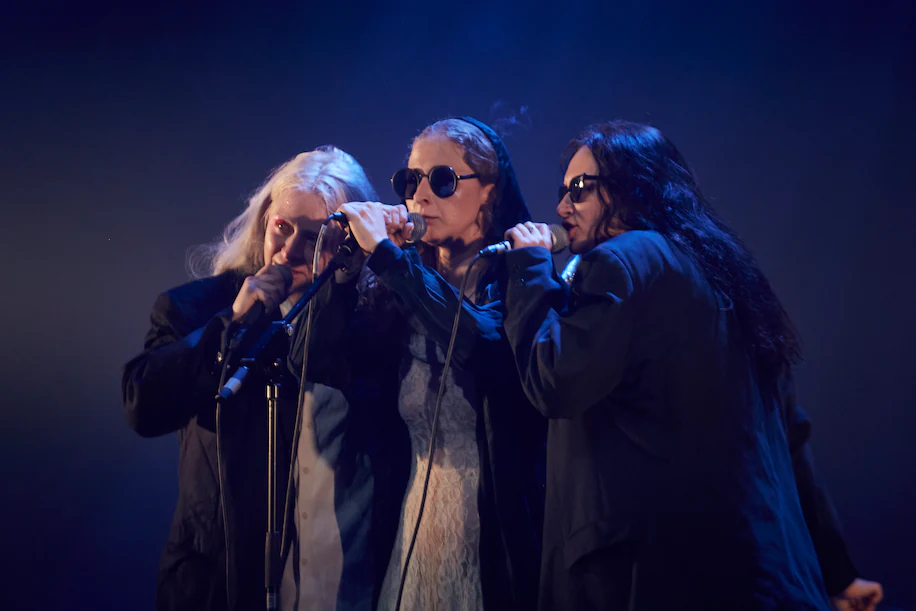

In the hectic lead-up to the Kling & Bang exhibition, Alyokhina, along with Pussy Riot’s Olga Borisova, Diana Burkot and Pletner, toured Europe with performances based on Alyokhina’s “Riot Days.” They performed in front of 100,000 people in Prague, headlining an outdoor street festival marking the anniversary of the Velvet Revolution, the nonviolent movement that ended communism in the former Czechoslovakia.

The final performance of the tour was in Iceland’s National Theater the night after the Kling & Bang opening. In front of a packed audience, the quartet chanted lyrics adapted from “Riot Days.” Burkot, the group’s musical core, thrashed away on drums and keyboard. She wore an orthopedic boot on one leg, having broken it earlier in the tour.

During one song, Borisova, a former police officer who has been part of Pussy Riot since 2015, repeatedly sprayed the audience with water. After an intense crescendo of punk-style screaming, flutist Pletner stood on a table at the back of the stage and again urinated on a Putinportrait. The show concluded with an antiwar, pro-Ukraine coda and a plea to donate money to a children’s hospital in Kyiv.

Back at the gallery the next day, Alyokhina sat scrolling through phone messages, puffing away on her vape pen. Her demeanor was cool, businesslike — hard to square with her ferocious stage presence the previous night. Kjartansson recalled the time someone in Alyokhina’s presence had mentioned Petr Pavlensjy, the Russian activist who nailed his testicles to Red Square. “Masha said, ‘Yes, but the nail only went through his skin.’” Kjartansson erupted in laughter.

“She’s made of something tougher than most of us are,” said Sigurjónsdóttir, who also said she admires the way Alyokhina “almost respects the system. She makes allies of people within it.”

I asked Alyokhina what the prime ministers of Iceland and Finland had said to her during their meeting.

“They were listening,” she said. “I told [Finnish Prime Minister] Sanna Marin about the importance of an embargo. This [war] is all made on European money. It’s so clear that without European money, [Putin’s] machine will not work. If Europe and the U.S. had imposed heavy sanctions in 2014 after the invasion of Crimea, 2022 wouldn’t have happened.

“The basis of European values is the importance of each life. Now Ukrainians are dying. Their whole energy system is collapsing. They are fighting out of pure bravery — it’s not because the sanctions are working.”

Leaders in the West, Alyokhina added, “are all afraid of a third world war. But just imagine one simple thing: If Ukraine loses this war, the Russian army will go again to Kyiv and what will happen next? How will we all live with this?”

Velvet Terrorism: Pussy Riot’s Russia through Jan. 15 at Kling & Bang gallery, Reykjavik, Iceland.